استرِح. تَفَكَّر. تأمَّل | بيتر ويست

ترجمة: هاشم الهلال - تحرير ومراجعة: بلقيس الأنصاري هَدَفَ كتاب سوزان ستبينغ الفلسفيّ، إلى إعطاء الجميع أدوات التفكير الحُرّ. "هناك...

T.S. Eliot’s last masterpiece, the Four Quartets, conveys a sense that our experience of time is the fragmentation of a timeless unity at the heart of our changing world.

Much of the book was written during the chaos of the Second World War. The poet remained in London during the Blitz, where he served as a volunteer fire watchman, tasked with preventing blazes from consuming buildings.

German bombers droned over the city, laden with high explosive and incendiary bombs designed to terrorise the English into submission. As the sound of sirens pierced the air, punctuated with the blasts of bombshells pounding buildings into rubble, the poet’s mind had turned to divinity.

The speaker of the poem longs for the sacred tranquillity and simplicity of the “still point of the turning world” — the middle of the axis of the turning universe in which we can find unity with the divine. Eliot described it as,

“Neither flesh, nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement. And do not call it fixity, Where past and future are gathered.”

Eliot strips away time and space, leaving a feeling vacated of positive expression and leaving only something that could be negatively defined, just beyond the reach of intelligibility. It’s the poetic expression of the mystical strains of Platonist philosophy that we now call Neoplatonism.

The genesis of this kind of Platonism lies in a chaotic time in the history of the Roman Empire, the so-called “crisis of the third century” (235–284 CE). It was a time in which political instability, war, mass-migrations, plagues and economic depression brought the Empire to its knees.

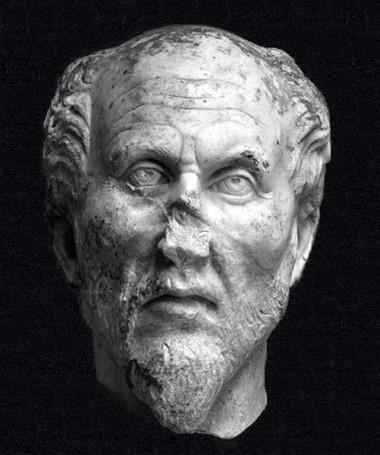

Plotinus, the founder of Neoplatonism, entered adulthood in a world of uncertainty and terror, and ended his life teaching the idea that the world is merely an image of a true reality that is eternal and good. His ideas radiated through the east and west, profoundly influencing the philosophical and theological traditions of Europe and Asia.

Plotinus was far from Rome when he set out on his philosophical career. He lived in Egypt, at the time a province of the Roman Empire. The philosopher was born in around 204 CE in the north of the country as a Roman citizen.

Egypt had been subsumed into the Hellenic (culturally Greek) world through hundreds of years of Greek and Roman rule. The once-mighty ancient Kingdom of the Pharaohs had been annexed by the Persians, and then conquered by Alexander the Great when he defeated the Achaemenid (Persian) Empire.

Upon Alexander’s death the territory became the Ptolemaic Kingdom under the control of a Greek dynasty. It was founded by one of Alexander’s generals, Ptolemy I Soter, in 305 BCE and lasted almost three centuries until Cleopatra VII’s apparent suicide in 30 BCE as her kingdom was overrun by a Roman army.

Greek was the official language of commerce and Greek and Roman religion and culture mingled with the well-established traditions and religions of Ancient Egypt, which the Ptolemaic dynasty had embraced. Roman Egypt had become a melting pot of eastern and western cultures, sciences and spiritual traditions.

Porohyry, the principal follower of Plotinus, tells us that the philosopher started studying relatively late at the age of twenty-seven. He travelled south to Alexandria — a commercial and intellectual centre in the eastern Roman Empire that had been established by, and of course named after, Alexander the Great.

Plotinus studied under the Platonist Ammonius Saccas and worked in Egypt for eleven years until he decided, at the age of thirty-eight, that he would like to learn more of the Persian and Indian philosophical and spiritual traditions.

He followed the army of Emperor Gordian III as it marched into Persian territory. The expedition was a disaster and Gordian was killed, either in battle or at the hands of his own guards. In the chaos that followed, Plotinus made his way back to Antioch, lucky to have escaped hostile territory with his freedom.

The philosopher made his way to Rome where he established a school and attracted notable students, including Porphyry. The philosopher became influential, gaining rich supporters who housed him, cared for his ailments and even left him legacies. One such admirer was the Emperor Gallienus, whose reign was relatively long (fifteen years), but fraught with civil war.

Plotinus attempted to persuade Gallienus to rebuild a ruined settlement in southern Italy known as the “City of Philosophers”, where the rule of Plato’s Laws would be implemented over a community of the philosophically-minded.

The project never came to fruition, probably a victim of the political chaos surrounding Gallienus’s difficult reign. The philosopher settled in southern Italy and committed himself to write a book for posterity.

Porphyry compiled and, it seems, heavily edited the book that would secure the legacy of Plotinus. If it were not for Porphyry, it’s doubtful we’d know much about Plotinus today.

The younger philosopher reported that Plotinus’s attempts to write the chapters were chaotic. His eyesight was failing and his handwriting was difficult to decipher.

Porphyry used Plotinus’s extensive lecture notes and essays to piece together a coherent work. The notes for the Enneads — the name is taken from the Greek ἐννέα: “group of nine” — were amassed over the last seventeen years of Plotinus’s life.

While Plotinus is labelled as a “Neoplatonist”, the philosopher likely thought of himself simply as a Platonist. The label of Neoplatonism is an invention of nineteenth-century historians. Plotinus himself had no intention of revising or adjusting the ideas of the Platonic tradition as that label implies, his ideas were — in his eyes — a way to teach Platonism.

The simplest principle of Platonism is the key to understanding Plotinus’s work; according to Plato, an eternal world of ideas is true reality as opposed to the illusory world of appearances that we inhabit.

There are three categories that structure reality in Plotinus’s understanding of the universe. These are described as the “three hypostases”, and they progress from absolute simplicity and more real to the multiple and less real. The hypostases are “the One”, Intellect (Nous), and Soul (Psyche).

The three hypostases that make up reality in its entirety are not thought by Plotinus to be new ideas. As far as the philosopher was concerned, these were simply expressions of Plato’s idea of reality.

Plotinus understood there to be an underlying substance of all things. This follows the Platonic idea that some things are more real than others. Animals are more real than man-made objects, for example, because animals have an intrinsic organic unity. The soul is more real than the animal because it is immaterial and not even composed of parts.

There is therefore an order of being, from low to high. From things that are more fragmented and accidental to things that are more unified and real. At the top of this hierarchy would be a supremely unified reality, a oneness that defies multiplicity.

This unity gives rise to multiplicity, as unity always does. Think, for example, of the number one as generative of all subsequent numbers (one plus one is two and so on). Different levels of being in the hierarchy cascade from this one source as a fountainhead of reality.

He described this unity as “the One”. The One is supreme and transcendent. It is self-caused and the cause of all things, the mystical source of reality. It cannot be divided nor does it stand as distinct in any way. The One is beyond categories of things in existence, and neither is it the sum of all things.

Plotinus describes the One as interchangeable with the “idea of the Good” in Plato’s Republic. It is indescribable and incomprehensible, yet known indirectly through our experience of life. What Plotinus is alluding to defies naming. The “One” is the least inadequate word to denote this unity, but to name it is to misrepresent it as a thing, when it is in fact transcendent of things.

The One is so fundamental that it cannot be predicated, to speak about the One is to make it part of other things, since language is by its nature relational. To say “the One is good”, for example, is to compromise its supreme unity because you are treating the One as a subject and giving it the predicate “good”.

But our existence is in a world of change and difference. How does the plurality of existence derive from the One? The answer, according to Plotinus, is “emanation” — all things emanate from the unity of the One by the next two stages: Intellect and then Soul.

This is not a division of oneness, nor is it successive stages of reality coming into being over time. It’s rather a matter of instantaneous derivation. Human beings know (but not necessarily comprehend) the world through these tiers of being at all instances. The three levels of reality are levels of contemplation of a single eternal reality.

Plotinus used a simple metaphor to compare the three hypostases. If the Divine Intellect is like the sun, the Soul is the moon, whose light is the reflection of the sun, then the One is light itself, pure and unchanging, a category unto itself.

The first derivation, “Intellect”, accounts for archetypes, or what Plato called “Forms”: the perfect intellectual forms from which real things derive.

For Plato, these forms are eternal and immutable. They transcend space and time and are the intuitive basis of knowledge. So the Intellect is the eternal and unchanging derivation of the One into parts. It is prior to our experience of the world yet structures our understanding of it through forms.

The most often used way to describe forms is the triangle. You can draw a triangle on a piece of paper with a pencil and the result would be a triangle only by virtue of its approximate resemblance to the archetypal triangle form.

The triangle on the piece of paper will be imperfect and changing — the lines will not be perfectly straight, the ink and the paper are changing over time — whilst the form of the Triangle is perfect and unchanging. But it is the intelligibility of the Form “Triangle” that actually allows us to draw a triangle since it is the idea “triangle”.

The third derivation is “Soul”. This corresponds to rational thinking and human experience.

Time is a product of nature’s inability to adequately contemplate divine unity. The Soul, unlike the Intellect, cannot contemplate forms in an instance but instead must contemplate them as fragmented objects perceived in moments of succession.

Time, like space, in this sense, is “distension” or fragmentation of the perfect and unchanging unity of One. The progress of time, manifested in change, is the breaking down of the unity of forms, which in turn are derived from the One. Plotinus describes time as a “thing seen upon the Soul, inherent, coeval to it, as Eternity to the Intellect.”

The derivation of Soul is split into two itself. There is a higher division and a lower division. The higher division of the Soul looks inwards towards the Intellect and contemplates the unchanging reality of that higher derivation. The lower division of the Soul is outer facing towards the material world, bodies and change.

The choice presented here is what underpins the ethical aspect of Plotinus’s (and Plato’s) philosophy: as rational human beings, we can choose to face inwards contemplate the eternal and good, or be mired in the changing world.

If the One is the source of all reality, and the One is identical with the supreme Good, then evil presents a problem. How can anybody or anything that is derivative of the Good be bad or evil?

Evil is simply the opposite of good for Plotinus. Matter is at the very limit of being, while the One is at the heart of it. If we turn our desire away from the unity of the Good at the centre of being and toward matter at the limit we are debasing ourselves. Matter is not inherently nor intrinsically evil, evil happens in the relation the soul takes to matter, being placed as it is between matter and the Good.

The soul is necessarily contemplative and active, the lure of the pure passivity of matter is as real and necessary as the Good to which souls are naturally drawn. Evil must exist by virtue of being the opposite to what is good.

All that is matter is merely an image of that which is its true and eternal archetype. The soul by right is the master of matter, but can come under the sway of matter and become a slave to what it should rule over.

Following from this, Plotinus warns against taking moral inspiration from other people since other people are simply part of the material world. He wrote:

“To model ourselves upon good men is to produce an image of an image: we have to fix our gaze above the image and attain likeness to the Supreme Exemplar.”

“Civic virtue”, then, is not good enough; to come close to perfection the student must take on a new life altogether, to turn inward toward the perfection of the forms.

Moral goodness is much like aesthetic beauty. The artist comes close to the natural unity of the Ideal Form, rallying parts from confusion into cooperation and harmony. “Idea is a unity and what it moulds must come to unity as far as multiplicity may.”

So too the student of morality must strive toward the Ideal and not merely copy that which is a copy. Plotinus, following Plato, sees salvation in philosophy, which is aimed at helping the student find communion with the One by means of contemplation.

This process is called “Henosis” and it essentially reverses the process of consciousness toward no thought at all, since all thought reflects only the illusions of the material world. Through Henosis, according to Plotinus, the soul can be:

“Cleared of the desires that come by its too intimate converse with the body, emancipated from all the passions, purged of all that embodiment has thrust upon it, withdrawn, a solitary, to itself again — in that moment the ugliness that came only from the alien is stripped away.”

The Soul cleansed through this process is “all Idea and Reason, wholly free of body, intellective, entirely of that divine order from which the wellspring of Beauty rises.”

Eliot’s Four Quartets describes but a brief glimpse of this idea — a momentary proximity to the divine:

“I can only say there we have been: but I cannot say where.

And I cannot say, how long, for that is to place it in time.

The inner freedom from the practical desire,

The release from action and suffering, release from the inner

And the outer compulsion, yet surrounded

By a grace of sense, a white light still and moving”

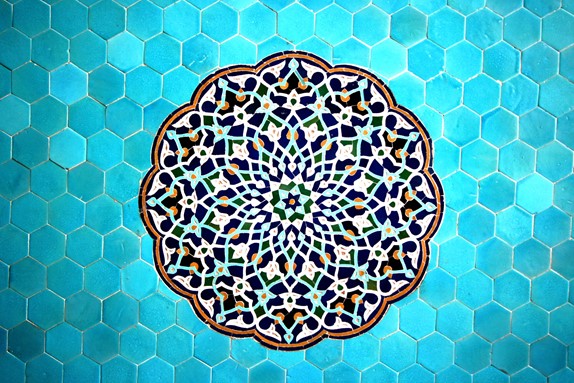

By structuring Platonic reality in the way he does, Plotinus more explicitly combines the mystical with the theoretical, giving the philosopher a good deal of influence over subsequent Islamic and Christian thinkers from Ibn Sīnā to Thomas Aquinas.

While Plotinus was a Roman pagan, the way he presents Platonism inspired thinkers and artists of the Abrahamic faiths to understand how multiplicity derives from the supreme oneness — and goodness — of God and the means by which we can come closer to that oneness.

The philosopher’s reported final words were: “Strive to give back the divine in yourselves to the divine in the all.”

ترجمة: هاشم الهلال - تحرير ومراجعة: بلقيس الأنصاري هَدَفَ كتاب سوزان ستبينغ الفلسفيّ، إلى إعطاء الجميع أدوات التفكير الحُرّ. "هناك...

يدعونا جون بول سارتر في رائعته «الكينونة والعدم» -التي كُتبت خلال الاحتلال النّازيّ لفرنسا- إلى تخيّل مشهدٍ من الحياة اليوميّة:...

في السنوات القليلة الماضية كانت الجامعات في قبضة سباق تسلُّح تقني مطَّرد مع طلابها، أو على الأقل مع الذين يُسلِّمون...

"ما يميّز هذه البلاد هو حرص قادتها على الخير والتشجيع عليه". - خادم الحرمين الشريفين الملك سلمان بن عبد العزيز...

«معنى»، مؤسسة ثقافية تقدّمية ودار نشر تهتم بالفلسفة والمعرفة والفنون، عبر مجموعة متنوعة من المواد المقروءة والمسموعة والمرئية. انطلقت في 20 مارس 2019، بهدف إثراء المحتوى العربي، ورفع ذائقة ووعي المتلقّي المحلي والدولي، عبر الإنتاج الأصيل للمنصة والترجمة ونقل المعارف.