الأملُ ليس تفاؤلًا | ديفيد فيلدمان – بنيامين كورن

ترجمة: محمد كزوّ - تحرير ومراجعة: بلقيس الأنصاري حتَّى عندما تعلَم أنّ الآفاق قاتمة، فالأمل يستطيع مساعدتك؛ إنَّه ليس مجرَّد...

“I really would like you here, my dear Baudelaire; they have been raining insults on me, I’ve never been led such a dance.”

Édouard Manet struggled with criticism for his entire career. The artist seemed for two decades to be a magnet for controversy. Unbeknownst to anybody at the time, Manet was controversial because he had unconsciously set off a revolution that would irrevocably transform western art.

His most notable works were scandalous not because of what subjects were depicted but rather how they were depicted. Manet is considered the first truly modern artist in western art, and some call him “the father of modern art”. That is precisely because he stood with one foot in the classic tradition. Manet worked in all the classic genres, from still lives to historical scenes, but did so with the intention to bring them into the modern world he lived in.

While his work seems haughty and often satirical, his letters to friends betray a man who was over-sensitive to the uproar he caused among the Parisian elites. He sought to honour the masters of the older ages in his work whilst also honouring the contemporary life around him. There was no way of achieving an ambition like that without rethinking the parameters of painting.

What makes Manet a liminal figure in western art is the profound difference between modern and classic art. Modern art is not “modern” by virtue of its newness or recency to our present moment, it is “modern” because it is fundamentally different from the art that preceded it.

All styles before modern art – Mannerism, Baroque, Rococo, Neoclassicism, Romanticism and Realism were exactly that: styles. Style is unconscious and often symptomatic rather than deliberate, it was most often identified after it had already infused itself in the visual language of art, as is the case with the Baroque style.

When it is consciously employed in what I’ll call “classic” painting (western European painting since the early Renaissance), style is a nuance. It’s like accenting speech. A sentence spoken with an accent still has its syntax and words, and the styled painting still has its subject matter and conventions of reproducing reality. What is left intact is a fundamental illusionism in classic painting, no matter what its style.

Classic painting is a virtual reality, an approximation of real things in space with the help of linear perspective, which is an optical trick to mimic the way we perceive objects in space. Just how those things are depicted – the style – in classic art is not a threat to that essential function of a painting as an optical illusion.

After Manet, something fundamentally changed. Styles of art gave way to “movements” in art. The Impressionists were first, and they were directly influenced by Manet. Many successive movements followed: Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Expressionism and more.

While these movements are often mistaken to be styles, they each sought to represent the world differently from each other and all painting before them. The “how” of depiction came to the foreground at the cost of painting being a virtual reality.

Painting continues to “represent” real things in modern art, but does not necessarily replicate the appearance of those things using optical tricks like linear perspective.

This is thanks to Manet.

The Academy

It’s important to understand how French art operated in Manet’s time in order to fully appreciate how he caused so much scandal. In the mid-nineteenth century, the only way an artist could really make a reputation was through the grand state-sanctioned public exhibitions of Paris.

The most prestigious exhibition was the Paris Salon, organised by the state-run Académie des Beaux-Arts (Academy of Fine Arts). As the world’s premier exhibition of contemporary art, the Paris Salon drew crowds from all over Europe and America. All artists aspired to be displayed at the Paris Salon, and Manet was no exception.

Awards and critical appraisal granted at the Paris Salon could make an artist’s career. The only problem was that an appointed jury determined what could and couldn’t be exhibited. These judges generally favoured the academic painting of former students of the Academy itself.

Academic painting was considered at the time a fusion of the Romantic and Neoclassical styles. Favoured painters such as William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Alexandre Cabanel were technically accomplished and could reproduce subjects with a photo-like precision and finish.

These painters reproduced scenes from mythology or history. The subjects were typically idealised. Bathers, nymphs, gods and goddesses were simply vessels of timeless qualities such as beauty, innocence or strength, rather than feeling like real human beings. Bouguereau commented that he could depict “war” but not “a war”.

In other words, the timeless forms of things were depicted, rather than those things as they played out in the real world. These timeless forms were depicted in a slick realistic way, using techniques like linear perspective to give the viewer the feeling that they are looking through a window into another reality.

Scandal

In 1863 the Paris Salon judging panel rejected two-thirds of the submissions. Frustrated artists asked Emperor Napoleon III to intervene. The Emperor invited the public to judge for themselves the rejected artworks by establishing the Salon des Refusés (“Exhibition of Rejects”). Among the rejected paintings was Manet’s Le Dejeneur sur l’Herbe (“The Luncheon on the Grass”), completed in that year.

The painting was Manet’s first public scandal. The Emperor himself said it was “an offence against decency.” It depicts a typical Parisian summer picnic comprising four adults, but one of them is naked. Two fully clothed men sit with the naked woman and converse, seemingly ignoring her. Behind this group a scantily clad woman in a chemise bathes in a stream. Whether she is part of the picnic or not is unclear as she seems detached from the group in the foreground.

It’s when we consider why the bather seems detached that we begin to see how this picture is so different from classic painting. She is too big to be where she is placed. Instead of looking like she is far behind the picnic, she seems to float above it. Manet hadn’t used linear perspective to distance the woman from the figures in the foreground. Instead, he has opted to distance her with summarising brushstrokes in hazy, pale shades.

You get the feeling looking at the painting that the woman behind may be part of a painted backdrop and that the three and their picnic are in fact sitting in the artist’s studio. Along with her companions, the nude is brightly lit from the front, as if under studio lights. The two men are wearing the kind of silky attire a well-heeled gentleman would wear in his lounge – the tasselled cap is a giveaway. Manet pays homage to the nude-in-nature scenes of old Italian masters like Georgione and Titian, while revealing that his homage is an elaborate and wholly artificial construction.

Manet used the language of classical painting to assert the modern world, and there was no more effective way of doing so than through the genre of the female nude. The nude was always a strange category in western art. Nudity for the most part was of course used to titillate male patrons, but the bare female figure somehow had to be shrouded in aesthetic legitimacy to conform with conventions of propriety and taste.

The nudes of academic painting were archetypes of ideal feminine beauty rather than women that could be imagined to be real. They were fantasy women of myth, posed by anonymous young models whose natural beauty is heightened further by the painter’s brush. They are submitted to the gaze of the painting’s viewer (presumed to be male) without much agency of their own. Classical nudes are there to be looked at and not to look back.

Manet’s nudes were women you could meet in the street. The giveaway of what makes Manet so modern is that he depicted his models as naked, not nude. But it wasn’t just the un-idealized depiction of the body that suggested this fact, it was in all the clues that Manet took the effort to include in his scenes. Manet’s nudes were unclothed bodies, rather than timeless bodies.

The nude in the foreground of Le Dejeneur sur l’Herbe, together with her male companions, is more solidly modelled in paint, her right foot rests on the inside of her clothed companion’s left ankle. Her clothes are heaped close to her reach, beside the basket of bread and fruit. She’s an actual person – Victorine Meurent – Manet’s regular model, recognizable in many of his paintings. Meurent would have been known and recognised by many in the crowds viewing the painting.

The frankness of the model’s nakedness caused consternation. There was an implicit suggestion in the painting that the scene may have something to do with prostitution in the Bois de Boulogne, a large country park in western Paris. But what was really confounding to the painting’s critics was perhaps the way the nude is “staged”, the way Manet doesn’t take the genre for granted but instead plays with its conventions.

Olympia

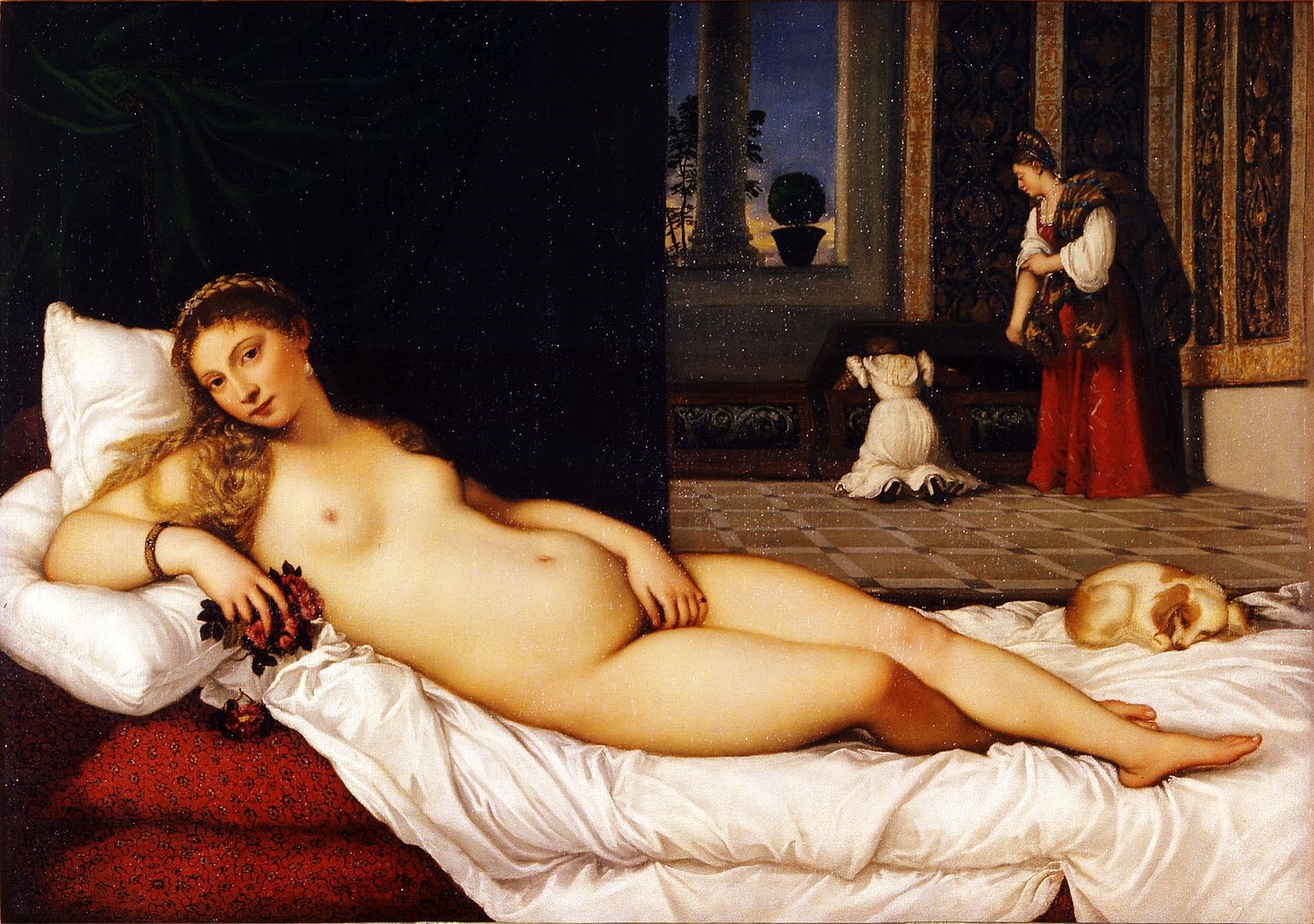

Only two years’ later another painting by Manet caused even more consternation at the Paris Salon itself. Olympia (1865) is a nude derived from Titian’s Venus of Urbino (c. 1534). The pose of the woman is basically the same, and various details of the painting are swapped for alternative counterparts: a black cat instead of the dog, an orchard instead of roses, a black maid bearing a bouquet of flowers takes the place of the servant.

In every instance of replacement Manet uses symbolism to convey the bare fact that Olympia is a prostitute. The name “Olympia” itself was a common pseudonym for sex workers. The dog, a symbol of fidelity, is replaced by a black cat, often a symbol of the prostitution. The ribbon choker, starkly black against her white throat, and the teetering slipper show a self-assured woman in the comfort of her habitat. These residual items of clothing make her definitively naked, not nude. A maid offers her a bunch of flowers, presumably the gift of a suitor, which she seems to ignore.

While the idealised nudes of classical art would coyly avert their gaze, Olympia gazes directly back at her viewer. The writer Émile Zola commented on the painting, “When our artists give us Venuses, they correct nature, they lie. Édouard Manet asked himself why lie, why not tell the truth; he introduced us to Olympia, this girl of our time, whom you meet on the sidewalks.”

The painting – given the honour of hanging at the Salon – was disparaged for what viewers perceived as a lack of talent. The painting was described by one critic as “A sort of female guerrilla, a grotesque in India rubber outlined in black, apes on a bed.”

The painting became a spectacle of mockery. “Never has a painting excited so much laughter, mockery and catcalls as this Olympia. On Sundays in particular the crowd was so great that one could not get close to it or circulate at all in the room.”

In keeping with Manet’s style, the figure of Olympia is rendered flatter than was typically expected of an artist. Just as in the case of Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe, Manet likely used bright studio lighting rather than natural daylight and so his figures are naturally not as well modelled as the figures typical in academic art.

As a result, critics compared Meurent to a cadaver on more than one occasion. A Victor Fournel described Olympia as being like “a corpse on the counters of the morgue […] dead of yellow fever and already arrived at an advanced state of decomposition.” A critic, Félix Deriège, wrote “This redhead is of a perfect ugliness. Her face is stupid, her skin cadaverous.”

Manet’s brushstrokes are undisguised, his work has a frankness of execution like a cabinet in which the joins and fastenings are visible. While academic art produced pictures of a virtual and idealised reality, Manet depicted real life in a way that made a virtue of the stuff of paint.

What caused such consternation? If Manet was simply a bad artist, why would critics attack him so ferociously? Why was the figure of Olympia herself attacked so vehemently?

Depictions of prostitutes did exist before Manet, and they existed in Academic painting. But these depictions were moral allegories, making a generalised point about selling sex. Manet resisted painting ideas and instead focused on the truth of the world around him. The truth was painful for his critics.

While the Venus of Urbino surrenders to the sexualised attention of her viewer, Olympia looks uninviting, her body is not freely available. The transaction between the courtesan and the client is made rudely implicit to a polite but hypocritical society in which respected men used the services of professional sex workers. The nude genre here is used not as a titillating window into a fantasy world, but a distillation of real social relations.

Manet was modern in both the senses that an artist can be modern. He took for his subject matter the people and the city around him and depicted them in a modern way. His models were real people and, in order that he did not consign them to the fantasy of illusionism and idealisation, he painted them with a sufficient amount of matter of factness: real lives inscribed in real paint.

Manet’s focus on real life, and his affiliation with the materiality of paint and its relationship with directly observed light was a primary inspiration to the Impressionists – the first widely influential “movement” of modern western art. The rest is history.

ترجمة: محمد كزوّ - تحرير ومراجعة: بلقيس الأنصاري حتَّى عندما تعلَم أنّ الآفاق قاتمة، فالأمل يستطيع مساعدتك؛ إنَّه ليس مجرَّد...

«لقد أثبتت السينما بأنّ لها قُدرة فائقة على التأثير. واليوم من خلال هذا المهرجان؛ نتعاون جميعًا لتعزيز اسم الخليج العربي...

لا عجبَ ألا يملك الأسقف بيركلي وقتًا للحسّ المشترك، فهو الرّجل الذي أنكر وجود المادّة. لقد اشتكى في كتابه «مبادئ...

إن الفلسفة غير معنية بالوضوح أو بتقديم أي إجابات واضحة عن الإنسان والعالم. هناك مقاربات وتيارات فلسفية هي أشبه بلعبة...

«معنى»، مؤسسة ثقافية تقدّمية ودار نشر تهتم بالفلسفة والمعرفة والفنون، عبر مجموعة متنوعة من المواد المقروءة والمسموعة والمرئية. انطلقت في 20 مارس 2019، بهدف إثراء المحتوى العربي، ورفع ذائقة ووعي المتلقّي المحلي والدولي، عبر الإنتاج الأصيل للمنصة والترجمة ونقل المعارف.