أختي مرآتي | ليلي دو

ترجمة: شوق العنزي - تحرير ومراجعة: بلقيس الأنصاري فانيسا وفيرجينيا مقربتان فنيًّا، خصومة في حالة حبّ. هل يمكن تجاوز الحسد...

One of the distinctive capacities of human beings is that we appreciate and desire beauty, as well as strive to create it. The creation of beauty is not limited to an artistic endeavor, but it can be recognized as the motivation of many of our daily gestures and concerns. We appreciate people who put care and effort into making the world of their life beautiful. At the same time, social wisdom suggests that there is something superficial in getting too caught up in mindlessly appreciating beauty as adornment, or appearance.

The history of philosophy, through Plato, Aristotle, and Kant, to name just a few of the most famous, gives beauty a place next to the concepts of the true and the good. These were thought to be the main universal values. In the 20th century, in Western culture, the attitude towards beauty changes dramatically both in philosophy and the artistic fields. On the one hand, few prominent philosophers find it worth thinking over the meaning of artistic judgement and experience; on the other hand, philosophers with interests in the artistic fields will predominantly argue that beauty is not an essential value for these fields.

The most prominent recent philosopher who dedicated his work to the research and the deciphering of the artistic concepts and experience, is Arthur Danto. According to Danto, “X is an art work if it embodies meaning.”[1] This definition of what a work of art is remarkable because it mentions nothing of ‘beauty’, which used to be the intrinsic purpose of the artistic creation. Danto celebrates that art finally moved away from identifying its purpose in the creation of beauty, after abusing of beauty throughout its entire history.[2]

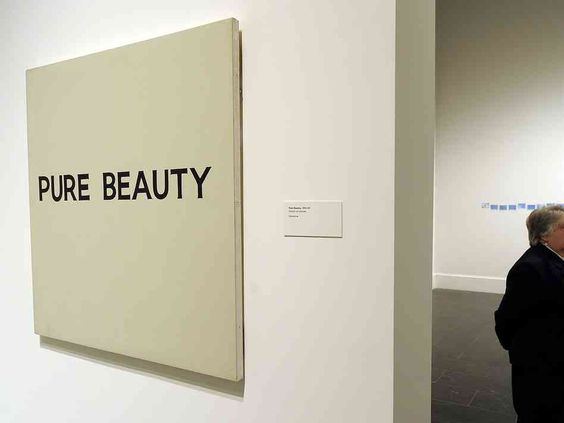

In his philosophical work, Danto only reflects on what he, and everybody else, notices is the case in the arts. Namely, that beauty lost popularity not only with philosophers, but with artists themselves. Art rebelled against the beauty requirement. The requirement that a work of art be beautiful started to be perceived as overwhelmingly addressing the senses to the detriment of the intellect. This requirement was understood at the beginning of the 20th century as threatening to reduce the work of art to a mere decorative object. John Baldessari, renowned conceptual artist who died very recently at 88 years of age, created the following work of art [3]:

A white canvas, on which one can read, in simple black capital letters, “PURE BEAUTY”. The painting does not address our senses, but rather our thought. Pure beauty is not presented here as the sensorially appealing, but as pertaining to the world of ideas. Another thing that this painting does not do, is to offer us an image that we are expected to find beautiful. This work of art refuses to offer beauty standards. The painting allows and invites each of us to fill in whatever our idea or image of beauty is.

There’s a variety of reasons for why artists and philosophers rejected the beauty requirement for a creative work to be considered art. One of them could be spelled out along the following lines: True art should attempt to widen one’s experience and understanding of the world. Rather than to serve people’s need for security and to reinforce habitual perspectives and standards, art should challenge one to consider new ways of seeing, or even force one to look at what they’d prefer to ignore. Beauty as the appealing, the pleasant, and the comfortable was for the most part left to the artisans, whose artifacts are to be hung up in living rooms, offices, and restaurants, or designed to adorn ourselves. Beautiful objects, pretty images, and expressions of artisanal skill are suited to be displayed in neutral spaces, or spaces used for rest and forgetting.

Artists felt like they were expected to depict an illusion of the world. They chose to be true to the experience that not everything in the world is beautiful, that there is meaning in what’s not immediately appealing in the world, and therefore that beauty is not the only artistic value, nor the most important artistic value. To limit artistic production to the illustration of beauty is to offer a distorted image of the world and of what is valuable. The beauty ideal is associated with bourgeois values and lifestyle, with the life of those who can afford to ignore suffering and the impossibility to live ideally.

Classical western art depicts suffering and death as edifying. It also has a preference for the suffering and death of heroes and of the famous and extraordinary people. Our awareness of suffering and of the inevitability of death is what prompts us to ask after the meaning of life, and whether there is more meaning to some lives than to others. We seem to be able to draw meaning from the death of heroes and of extraordinary people, and their suffering seems to be justifiable. But we ignore that extraordinary people live also anonymously, and that they might not find their own suffering and mortality as justified and comforting as we do. It is more difficult to associate anonymous suffering and death with beauty, or to find meaning in it. That we are mortal is what we want to forget. It is comforting to be able to say that some death and suffering is meaningful, gives one hope by seeming to promise immortality. But most death and suffering is the mere expression of mortality, of broken ideals and failed hope.

I think that there is a parallel to be drawn between the old-fashioned requirement that art is to account for the beauty of the world, and the necessary happy-ending of mainstream Hollywood movies. Both criteria speak of a naïve and overly-optimistic stance on the world, where death does not necessarily mean mortality, and where there’s no real reason for suffering, because … everything will turn out right in the end.

However, the concept of beauty does have some contemporary defenders. The philosopher who comes first to mind is Roger Scruton. Scruton argues that beauty is an essential human value to be pursued both in the everyday and as an artistic expression.[4] Scruton argues, in traditionally Platonic and Kantian fashion, that the quest for beauty is a spiritual one, and that a life which does not strive towards beauty, which does not hope of beauty, has lost its meaning.[5] His view on beauty is part of his self-professed conservatism. And if Scruton is right that a life devoid of the experience of true beauty is a life devoid of meaning, then the conclusion has to be that the lives of less lucky people are not worth living. This conclusion is not only sad, but simply false, because there are many other things that make life worth living, there are many things that offer spiritual edification, other than those which participate to Scruton’s elitist definition of the beautiful.

There is beauty in the day-to-day simplicity of things, of anonymous kindness and love, in lives lived without awareness of the grand beauty created by universal masters. There is beauty that commands respect and admiration in expressions of love and care that are not aimed at immortality. There is beauty in the humble acceptance of one’s mortality, and in living without the need to think of oneself as special in any way. One can be a super-human by exceeding average creative capacities in producing sophisticated, grand beauty and so reaching toward immortality. And one can be a super-human by having no pretention in being ideal and no hope in becoming immortal.

The quest for and recognition of beauty is an expression of our need to hope for better, of our capacity to be ideal, and of our humble awe in witnessing the miracle of existence and of gratuitous goodness.

[1] Arthur Danto, The Transfiguration of the Commonplace: A Philosophy of Art. 1981.

[2] See Arthur Danto, “The Abuse of Beauty”, Daedalus Vol. 131, No. 4, On Beauty (Fall, 2002), pp. 35-56.

[3] I found this image from the following web link, where you can also find a short conversation on Baldessari’s work: https://www.npr.org/2013/03/11/173745543/for-john-baldessari-conceptual-art-means-serious-mischief

[4] See, for example, his short book on beauty: Roger Scruton, Beauty: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2011.

[5] The documentary Why Beauty Matters?, is a detailed exposition of Scruton’s views on beauty: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bHw4MMEnmpc

ترجمة: شوق العنزي - تحرير ومراجعة: بلقيس الأنصاري فانيسا وفيرجينيا مقربتان فنيًّا، خصومة في حالة حبّ. هل يمكن تجاوز الحسد...

ترجمة: محمد كزوّ - تحرير ومراجعة: بلقيس الأنصاري حتَّى عندما تعلَم أنّ الآفاق قاتمة، فالأمل يستطيع مساعدتك؛ إنَّه ليس مجرَّد...

«لقد أثبتت السينما بأنّ لها قُدرة فائقة على التأثير. واليوم من خلال هذا المهرجان؛ نتعاون جميعًا لتعزيز اسم الخليج العربي...

لا عجبَ ألا يملك الأسقف بيركلي وقتًا للحسّ المشترك، فهو الرّجل الذي أنكر وجود المادّة. لقد اشتكى في كتابه «مبادئ...

«معنى»، مؤسسة ثقافية تقدّمية ودار نشر تهتم بالفلسفة والمعرفة والفنون، عبر مجموعة متنوعة من المواد المقروءة والمسموعة والمرئية. انطلقت في 20 مارس 2019، بهدف إثراء المحتوى العربي، ورفع ذائقة ووعي المتلقّي المحلي والدولي، عبر الإنتاج الأصيل للمنصة والترجمة ونقل المعارف.