الأملُ ليس تفاؤلًا | ديفيد فيلدمان – بنيامين كورن

ترجمة: محمد كزوّ - تحرير ومراجعة: بلقيس الأنصاري حتَّى عندما تعلَم أنّ الآفاق قاتمة، فالأمل يستطيع مساعدتك؛ إنَّه ليس مجرَّد...

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boëthius – known to us as Boethius – was one of the richest and most powerful men in the Kingdom of Italy in the late Latin era. He was the Magister officiorum (“Master of the Offices”): the senior administrator of court, commander of the palace guard and chief of the Roman bureaucracy.

At the time the Western Roman Empire had largely crumbled but Roman authority remained as the Ostrogothic kings of Italy – who ruled over the Goths and the Romans – respected its customs and law. These kings, having taken the empire from within, ruled through the Roman system rather than over it, preserving its institutions of political authority.

Boethius had also served as a senator and consul on the way to the apex of a uniquely prestigious political career. His father was a consul and so too were his two sons. The statesman was also a prominent scholar who translated a number of classical Greek works into Latin. In doing so, he preserved many great works of antiquity for Medieval Europe.

Disaster struck for Boethius in 523 AD when the king he was serving – Theodoric the Great – imprisoned him on the charge of treason. Boethius had merely come to the defence of a Senator named Albinus who had been charged with the same offence. While he was imprisoned and awaiting a brutal execution for a crime he did not commit, Boethius wrote his last work, The Consolation of Philosophy. In the face of death Boethius composed his philosophical testament, his last gift to the world.

The book became one of the most influential works of literature in the Middle Ages. Boethius’s masterwork inspired and influenced many great writers including Dante and Chaucer. It was translated into several languages by notable translators that included Queen Elizabeth I of England among them.

The book begins with Boethius left broken by his terrible fate. He is imprisoned, terrified and angry with his accusers, writing a poem of despair. He claims he has been wrongly accused and laments the terrible turn of events with the help of the muses of poetry.

But then a woman appears in the room with a “countenance exceeding the venerable”, wearing a beautifully decorated garment. On her frayed garment (“torn by the hands of marauders”) was woven in the Greek letter Π [Greek: Pi], on the topmost the letter θ [Greek: Theta], and between the two were to be seen steps, like a staircase, from the lower to the upper letter. The first letter represents practical philosophy and the latter represents contemplative philosophy. Her height varies – sometimes she is of average height, sometimes she towers high. She holds books in her right hand and in her left she holds a sceptre.

The woman is the personification of Philosophy, sometimes known as Lady Philosophy or Philosophia. In her God-like appearance, she resembles Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom. She had come to console Boethius over his fate. Five chapters of dialogue follow in which Boethius explores happiness, fortune, the nature of God and free will. The dialogue takes place between Boethius (it seems) and Philosophy but both are the mouthpieces of Boethius. With this in mind, I will describe the interlocutors as the Prisoner and Philosophy for the sake of clarity.

Although Philosophy visits the Prisoner to console him, she does not offer sympathy but instead demonstrates why he has no good reason to complain about his fate. In doing this Boethius shows that we have control over the way we respond to our fortunes but not over our fortunes themselves. To be at peace, we must understand that our mind is the only thing we have control over.

Fortune

Philosophy tells the prisoner that she has come to his aid as he suffers from the sickness of being too attached to earthly possessions. Philosophy assures him that the “gifts” of fortune are never yours but merely loaned to you. These gifts can be taken away as quickly as they are given.

Prosperity, power, status, family and public honour are things that never truly belong to any person. The personification of Fortune (Fortuna), appears to the prisoner to tell him as much herself:

“I can say with confidence that if the things whose loss you are bemoaning were really yours, you could never have lost them.”

The gifts of Fortune comprise what most of us today regard as the keys to happiness. Yet possessions and status are the things in our lives that are most easily lost. These are also the things that make us stressed and anxious as we seek to attain and hold on to them, knowing of the threat that hangs over everything we gain in these areas of our lives.

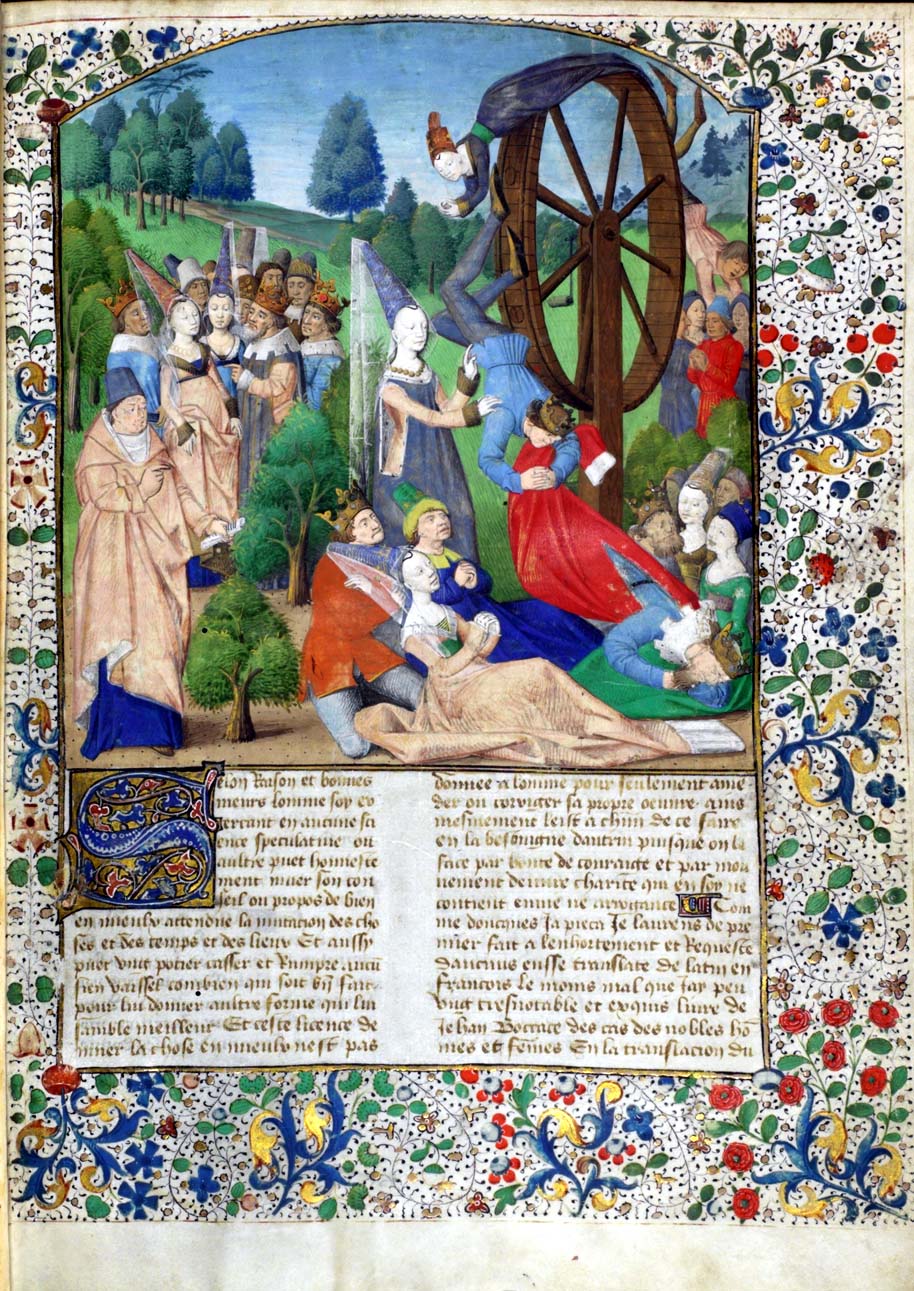

Philosophy describes the “Wheel of Fortune” to which we are all fixed. Fortune turns the wheel with abandon. Men who are at one moment at the heights of success and favour can descend in one turn to defeat and pain, just like Boethius himself had. “If you are trying to stop her wheel from turning, you of all men are the most obtuse,” she says to Boethius, “You are seeking to regain what does not belong to you.”

What’s more, fortune is relative: what a wealthy person would consider to be uncomfortable, a poor person would consider a luxury. The Prisoner can find contentment as long as they don’t attach happiness to the things fortune throws their way, but instead finds happiness in the consistency of their being. “All luck is good luck,” she tells him, “to the man who bears it with equanimity.”

Happiness

To show that happiness is within the prisoner’s reach, Philosophy distinguishes between the goods of fortune, which are of limited value and subject to fate, and the things that are truly good: virtue and sufficiency.

Boethius must stop trusting in anything that Fortune can take away at once. The prisoner was well aware that “there is no constancy in human affairs, when a single swift hour can often bring a man to nothing.”

So Philosophy teaches the Prisoner that, “If you are in possession of yourself you will possess something you would never wish to lose and something Fortune could never take away…. Happiness cannot consist in things governed by chance.”

Philosophy shows that we should not fix our desires on worldly things subject to the turning Wheel of Fortune. We should instead retreat to our self-sufficient reason to find tranquillity. This is what the Stoics called our “inner citadel” – the inner part of our selves that cannot be touched by extraneous events. Our capacity to reason cannot be affected by the ups and downs of fortune.

“The only way one man can exercise power over another is over his body and what is inferior to it, his possessions. You cannot impose anything on a free mind, and you cannot move from its state of inner tranquillity a mind at peace with itself and firmly founded on reason.”

These ideas are almost certainly taken from Stoics such as Epictetus and Seneca, whose writings Boethius would have been familiar with.

While much of the dialogue on fortune reflects Stoic teachings, Plato looms large as an influence on Boethius’s ideas on happiness. Philosophy demonstrates to the Prisoner that perfect good and perfect happiness are the same thing, and that they are, in turn, identical with God. To be truly happy, then, is to be entirely untouched by earthly fortune and close instead to God.

God is presented as a non-interventionist deity. All that exists is ordered simply because God exists, all things orient themselves to God. The human being, to act in accordance with nature exercises their reason to attain sufficiency and virtue and therefore, happiness, which is placing oneself with God.

When we seek material goods, reputation and relationships, we are really desiring virtue and sufficiency. Philosophy tells the philosopher that within us there is a desire for perfection but that desire is often misplaced. These misplaced desires are what can lead to evil. Both the virtuous and the evil desire“the good” but only the virtuous reach it.

Evil

Happiness and the ultimate good are made identical to Boethius. To be wholly virtuous is to be complete and to be complete is to be happy. To commit evil is to become less human and lose connection to God. The actions we undertake place us in a hierarchy of being either closer to or further from God.

“[T]hat those creatures who have an innate power of reason also have the freedom to will or not to will, though I do not claim that this freedom is equal in all. Celestial and divine beings possess clear-sighted judgement, uncorrupted will, and the power to effect their desires.”

The Stoics described this as acting in accordance with nature by fulfilling the Oikeiôsis – “orientation” – of being human, which is to be rational (a quality no animal is in possession of). The person who acts rationally, and therefore morally, is more human and free than the person who acts irrationally:

“Indeed, the condition of human nature is just this; man towers above the rest of creation so long as he recognizes his own nature, and when he forgets it, he sinks lower than the beasts.”

Philosophy makes the case that evildoers are only harming themselves by being evil. They lose their freedom because freedom is only realised when we act in accordance to the ultimate good. The desire for worldly pleasures is not acting in accordance with our nature. As already mentioned, Boethius makes no distinction between the rational and the good.

According to Philosophy, we are acting in free will only when we use reason to come to decide on our choices. If we are rational when we make our decisions we are acting in accordance with nature and therefore in our own interests – we are pursuing “the good”. Those who live in virtue – even if poor – are more powerful in spirit than those who do evil.

If our decisions are motivated by factors external to our own reason, such as desiring worldly things and a better reputation for ourselves, then we are not acting entirely in free will. The more rational we are, the freer we are as agents to act and choose. Irrational desires can make slaves of us if we allow them to.

“Human souls are of necessity more free when they continue in the contemplation of the mind of God and less free when they descend to bodies, and less still when they are imprisoned in earthly flesh and blood. They reach an extremity of enslavement when they give themselves up to wickedness and lose possession of their proper reason.”

Free Will

Book 5 of The Consolation of Philosophy is the most interesting to contemporary philosophers because it is the part of the book that can be considered original thought on the part of Boethius.

The arguments relating to fortune and happiness are an interesting composite of Stoic, Aristotelian and Platonic thought. These ideas show the importance of Boethius in transmitting classical philosophy to Medieval Europe. But the argument he puts forward for free will in this part of the dialogue is likely to be his own.

The Prisoner challenges Philosophy on the point of free will. Both the Prisoner and Philosophy accept that God exists and that God is omniscient – all-knowing of all past, present and future events. But if God has a timeless perspective and knows all things and events simply and singly, then it seems to follow that future events happen necessarily because they are known by God before they happen and because they cannot not happen. In other words, there is an incompatibility between an event not having a necessary outcome, yet its outcome being known.

If God is omniscient, then it is difficult to maintain any meaningful degree of human freedom. Without freedom there seems to be no convincing way of defending God against charges of creating suffering for human beings. How can God judge us for acts that He knows we were destined to commit before we were even born? People cannot be held responsible for their actions if they cannot choose them.

Philosophy answers the Prisoner’s questions by making the distinction between divine prescience and divine predetermination. Philosophy tells the prisoner that God is eternal because God exists outside of time. God is a-temporal. All of time and the events which happen within it is present to God. “Eternity,” she tells him, “is the possession of endless life whole and perfect at a single moment.”

Our common understanding of eternity is something that is present throughout all time. Such a thing would exist in time. But to exist in time is to be imperfect. God is not older than the world in time, since time itself was created by God.

Philosophy makes the distinction in this way:

“[I]f we want to give things their proper names, let us follow Plato and say that God is eternal, the world perpetual.”

If God existed in time and is perpetual as opposed to eternal, His understanding of the future would be like our understanding of the past. God does not know the future as we know the past, God knows all things in the present as we – who live in time and not eternity – know our present.

“Why, then, do you insist that all that is scanned by the sight of God becomes necessary?” Philosophy asks the Prisoner. “Men see things but this certainly doesn’t make them necessary. And your seeing them doesn’t impose any necessity on the things you see present, does it?”

Through this logic, Philosophy maintains that God is still omnipotent and omniscient while retaining the human capacity to choose. God does not cause the events he foreknows. He knows them because they happen in the immediacy of His sight over all things, rather than their happening because God foreknows them.

The problem here, the Prisoner points out, is that if we do have free will and God knows our actions before we act, then our actions cause God’s knowledge. This would entail that God is not perfect. It is “back to front”, the Prisoner claims, to think that “the outcome of things in time should be the cause of eternal prescience.” To this Philosophy responds that while a future event may be made necessary by God’s knowledge of it, it is free and undetermined when considered in its own nature. Some events are fated by their very nature.

The sun shining, for example, is a “simple necessity” we’d ascribe to the sun – it must shine by its nature. The act of walking isn’t a simple necessity like the sun having to shine is, we have a choice over whether we take that walk or not. A woman has chosen to walk. However, to God the woman is necessarily walking, because she is walking. At the moment she is walking, the woman cannot not be walking, because this would be a contradiction. But the act itself is a free one.

From God’s perspective our actions are necessary, but God’s knowledge of our actions is a conditional necessity of their happening. We are therefore free in the sight of God, yet we do not cause God’s knowledge with our actions since God’s knowledge is a condition of our actions. The sun cannot help but shine, it has no free will, but human beings are free to choose their attitudes and actions.

Crisis and Consolation

The Consolation of Philosophy is a book borne of personal and civilisational crisis. Boethius had been sentenced to death in part because of a schism within Roman civilisation. Relations between Theodoric the Great and Justin I, the emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire, had fallen apart. Boethius was alleged to have been part of a Roman plot to oust the Ostrogoths, who were predominantly of the Arian faith, considered heretical by the Roman Christians.

Boethius is often described as “the last Roman”. The statesman was from a distinguished and powerful aristocratic Roman family (the gens Anicia) that could trace its roots back to the Republic. It would not be lost on Boethius that the classical world, of which he was a part, was dead. The English philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote that Boethius “would have been remarkable in any age; in the age in which he lived, he is utterly amazing.”

His imprisonment interrupted a lifelong ambition to translate (with commentary) all the works of Aristotle and Plato. So it was his executioners who deprived Medieval Europe of many important classical works. Instead, they were preserved by the Byzantines and Arabs of the East, only to find western readers during the Renaissance. Theodoric died soon after Boethius and his kingdom was torn apart by succession disputes and invasions. Europe sank into several centuries (circa 5th to 10th centuries) of intellectual and cultural regression now known as the “dark ages”.

The book is ultimately about transcendence. The staircase depicted on Philosophy’s garment is a fitting metaphor. Sitting out a prison sentence that would end with torture and execution, Boethius attempts to transcend his worldly existence through reason. For Boethius, we can truly understand the true order of the world only if we attain a divine – and therefore eternal – perspective on things.

We can understand, he believed, that our troubles are part of a greater whole – the provident workings of God, the greatest good. All things are ultimately reconciled in eternity. Even evil does not really exist in the greater scheme of things. Evil is merely a deprivation, and not a power unto itself since God is all-powerful and God is good.

While many of the ideas in The Consolation of Philosophy may have lost their power in the centuries since, the sheer ambition and breadth of the work make it a wonder of the Medieval world. Many of the themes discussed by Boethius are still puzzling to philosophers and psychologists to this day – free will, the problem of evil, the nature of justice and the origin and purpose of our desires.

Imprisoned in the shadow of death and among the ruins of the classical world, Boethius addressed these questions from the heights of reason. In its poetic beauty and through its magisterial construction of reasoned argument, the book remains a consolation for whatever troubles we face. The book often refers to the power of good, its own power is undeniable.

ترجمة: محمد كزوّ - تحرير ومراجعة: بلقيس الأنصاري حتَّى عندما تعلَم أنّ الآفاق قاتمة، فالأمل يستطيع مساعدتك؛ إنَّه ليس مجرَّد...

«لقد أثبتت السينما بأنّ لها قُدرة فائقة على التأثير. واليوم من خلال هذا المهرجان؛ نتعاون جميعًا لتعزيز اسم الخليج العربي...

لا عجبَ ألا يملك الأسقف بيركلي وقتًا للحسّ المشترك، فهو الرّجل الذي أنكر وجود المادّة. لقد اشتكى في كتابه «مبادئ...

إن الفلسفة غير معنية بالوضوح أو بتقديم أي إجابات واضحة عن الإنسان والعالم. هناك مقاربات وتيارات فلسفية هي أشبه بلعبة...

«معنى»، مؤسسة ثقافية تقدّمية ودار نشر تهتم بالفلسفة والمعرفة والفنون، عبر مجموعة متنوعة من المواد المقروءة والمسموعة والمرئية. انطلقت في 20 مارس 2019، بهدف إثراء المحتوى العربي، ورفع ذائقة ووعي المتلقّي المحلي والدولي، عبر الإنتاج الأصيل للمنصة والترجمة ونقل المعارف.