الأملُ ليس تفاؤلًا | ديفيد فيلدمان – بنيامين كورن

ترجمة: محمد كزوّ - تحرير ومراجعة: بلقيس الأنصاري حتَّى عندما تعلَم أنّ الآفاق قاتمة، فالأمل يستطيع مساعدتك؛ إنَّه ليس مجرَّد...

– It is my honor to welcome Professor Nicholas Maxwell to the Mana platform. First, we‘d like to express our gratitude to you for accepting this dialogue. As you are a philosopher of science in one of the greatest universities in the UK (UCL), how can you introduce yourself to the reader in the Middle East?

Thank you so much for inviting me to the Mana platform! I am delighted to have the opportunity to answer your questions about my work.

I have devoted much of my working life to arguing that we need to bring about a revolution in universities so that they come to seek and promote wisdom, and do not just acquire knowledge. Long ago, in 1984, I published From Knowledge to Wisdom: A Revolution in the Aims and Methods of Science, Basil Blackwell, Oxford (2nd ed., 2007); available free online at https://philpapers.org/rec/MAXFKT-2 . That book spells out the basic message in detail. When first published, it was widely and favourably reviewed – it got a glowing review in Nature – but since then it has been somewhat neglected. For the last 45 years or so, I have done what I can to get a hearing for my basic message, in book after book, article after article, lecture after lecture. We face grave global problems: population growth; destruction of natural habitats, loss of wild life and mass extinctions; war and the threat of war; the menace of nuclear weapons; pollution of earth, sea and air; the current pandemic; and most serious of all, perhaps, the impending disaster of climate change. Universities ought to be devoted to helping us discover what we need to do to resolve the conflicts and global problems that menace our future. But that is not what universities do. Instead, they devote themselves to the pursuit of knowledge. If we are to make progress towards a better world, we need to learn how to do it. That in turn requires that universities are devoted to the task. At present, they are not. That is why we need an academic revolution so that the basic task becomes, not just to acquire specialized knowledge, but rather to help humanity acquire wisdom.

– You have lots of papers and books, essays, additionally, you have contributed to books, also you have a rich website, what sort of feeling do you have when you are writing in philosophy of science, and when you are teaching courses?

In connection with my work, there have been times of exhilaration when, it has seemed to me, I have made an important discovery. This happened, long ago, when I made a discovery about how to resolve the conflict between what physics tells us about the world, and the world we experience and live in. It happened when I made what seemed to me an important discovery about the nature of science: in order to make sense of science, we need to see science as adopting a metaphysical (that is empirically untestable) assumption about the nature of the universe: it is, in some way or other, physically comprehensible. It happened when I realized that the basic aim of universities ought to be to seek and promote wisdom and not just acquire knowledge.

Sometimes, writing up what I thought I had discovered, was also an exhilarating experience. This was certainly the case in connection with my first book, What’s Wrong With Science?, Bran’s Head Books, 1976 (available online free at https://philpapers.org/archive/MAXWWW-6.pdf ). Most of this book is in the form of a furious argument between a scientist and a philosopher. I wrote the book in three weeks to meet the publisher’s deadline. At last I was expressing what I had struggled to communicate for some four years. I foolishly thought this book would change the world. Nothing of the kind happened! Writing my second book was very different. I laboured and laboured over it, struggling to express what I had to say in as clear a way as possible.

At other times, I have felt a sense of weariness, because I am arguing for my basic thesis – universities need to seek and promote wisdom, and not just acquire knowledge – something I have already argued for many times in the past, even if in different ways.

I have published an autobiographical account of my intellectual life, from my childhood to my times at UCL, my discovery of the idea that universities ought to seek wisdom, not just knowledge, and beyond. It is called Arguing for Wisdom in the University: An Intellectual Autobiography, Philosophia, 2012, vol. 40, no. 4, pp. 663-704, available free online at https://philpapers.org/rec/MAXAFW . In this intellectual autobiography, I make clear how much I owe to the work of Karl Popper.

As for teaching at UCL, I was always very fortunate to be able to teach what my research was about, and to run my courses as discussion seminars. One course I gave at UCL explored the problem: How does the world we experience and live in exist and best flourish embedded as it is in the physical universe? Another course explored the problem: What ought to be the aims and methods of science? What, more generally, ought to be the aims and methods of academic inquiry?

– You have claimed that we ‘need a revolution in the aims and methods of academic inquiry’ what do you mean exactly with the word ‘revolution’?

By “revolution” I mean simply “radical change”. We need a radical change in the aims and methods of academic inquiry, so that, instead of seeking specialized knowledge, academic inquiry comes to seek and promote wisdom – wisdom being the capacity, active endeavour and desire to realize (experience and achieve) what is of value in life for oneself and others – wisdom thus including knowledge and technological know-how, and much else besides. Elsewhere, I have drawn up a list of 23 structural changes that need to be made to universities if they are to change radically so that what we have at present – “knowledge-inquiry” – becomes what we need – “wisdom-inquiry”: see https://www.ucl.ac.uk/from-knowledge-to-wisdom/whatneedstochange .

Such a radical change in the nature of universities could only be brought about as a result of considerable discussion and debate. My own university, UCL, has recently made some steps away from knowledge-inquiry towards wisdom-inquiry. It has instigated “The Grand Challenges Programme”, which seeks to bring specialists together to help solve global problems: see https://www.ucl.ac.uk/grand-challenges/. This programme has been influenced by my work. Similar initiatives have arisen in other universities.

– Philosophically speaking, is it true that our fundamental problem (I think this is the title of your book in 2020) is how can we reach the global philosophy? In addition, how is this kind of philosophy you see today different from the previous kinds?

Yes, I have just published a book called Our Fundamental Problem: A Revolutionary Approach to Philosophy, June 2020, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal. In a way, this book sums up what I have been thinking about for the last 80 years. (I started thinking about these problems when I was about 4 years old.) In effect, I answer your questions in the Preface. This is what I say in the preface:-

How can our human world – the world we experience and live in – exist and best flourish embedded as it is in the physical universe? That is our fundamental problem. It encompasses all others of science, thought and life. This is the problem I explore in this book. I put forward some suggestions as to how aspects of this problem are to be solved. And I argue that this is the proper task of philosophy: to try to improve our conjectures as to how aspects of the problem are to be solved, and to encourage everyone to think, imaginatively and critically, now and again, about the problem. We need to put the problem centre stage in our thinking, so that our best ideas about it interact fruitfully, in both directions, with our attempts to solve even more important more specialized and particular problems of thought and life.

The book is intended to be a fresh, unorthodox introduction to philosophy – an introduction which will, I hope, interest and even excite an intelligent 16 year old, as well as any adult half-way interested in intellectual, social, political or environmental issues. Scientists and professional philosophers should find it of interest as well. The idea of the book is to bring philosophy down to earth, demonstrate its vital importance, when done properly, for science, for scholarship, for education, for life, for the fate of the world.

If everything is made up of fundamental physical entities, electrons and quarks, interacting in accordance with precise physical law, what becomes of the world we experience – the colours, sounds, smells and tactile qualities of things? What becomes of our inner experiences? How can we have free will, and be responsible for what we do, if everything occurs in accordance with physical law, including our bodies and brains? How can anything be of value if everything in the universe is, ultimately, just physics? These are some of the questions we will be tackling in this book.

These questions arise because of this great fissure in our thinking about the world. Our scientific thinking about the physical universe clashes in all sorts of ways with our thinking about our human world. The task is to discover how we can adjust our ideas about both the physical universe, and our human world, so that we can resolve clashes between the two in such a way that justice is done both to what science tells us about the universe, and to all that is of value in our human world – the miracle of our life here on earth – and the heart-ache and tragedy.

It is all-but inevitable that even the smallest adjustments to what we take science to tell us about the universe, or to what we hold to be the nature and value of our human world, will have all sorts of repercussions, potentially, for all sorts of fields outside philosophy – for science, for thought, for life. And indeed revolutionary ideas do emerge in this book from the exploration of our fundamental problem.

There is, first, a revolution for philosophy. A new kind of philosophy emerges which I call Critical Fundamentalism. This tackles our fundamental problem, and in doing so seeks to resolve the fundamental fissure in the way we think about the universe and ourselves in such a way that this resolution has multiple, fruitful implications for thought and life. Second, there is a revolution in what we take science to tell us about the world: it is concerned, not with everything about everything, but only with a highly specialized aspect of everything. This is the subject of chapter 3. Third, there is a revolution in our whole conception of science, and the kind of science we should seek to develop – the subject of chapter 4. Fourth, there is a revolution in biology, in Darwin’s theory of evolution, so that the theory does better justice to helping us understand how life of value has evolved. This is the subject of chapter 5. Fifth, there is a revolution in the social sciences. These are not sciences; rather, their proper basic task is to promote the cooperatively rational solving of conflicts and problems of living in the social world. In addition, they have the task of discovering how progress-achieving methods, generalized from those of natural science (as these ought to be conceived) can be got into social life, into all our other social endeavours, government, industry, the economy and so on, so that social progress towards a more enlightened world may be made in a way that is somewhat comparable to the intellectual progress in knowledge made by science. Social inquiry emerges as social methodology or philosophy and not, fundamentally, social science. Sixth, there is a much broader revolution in academic inquiry as a whole. We need a new kind of academic enterprise rationally designed and devoted to helping us resolve the grave global conflicts and problems that confront us: habitat destruction, loss of wild life, extinction of species, the menace of nuclear weapons, the lethal character of modern war, gross inequality, pollution of earth, sea and air, and above all the impending disasters of climate change. These problems have arisen in part because of the gross structural irrationality of our institutions of learning devoted as they are to the pursuit of knowledge instead of taking, as their basic task, to help humanity resolve conflicts and problems of living in increasingly cooperatively rational ways, thus making progress towards as good, as wise, a world as possible. Seventh, there is the all-important social revolution that might gradually emerge if humanity has the wit to develop what it so urgently needs: academic inquiry rationally devoted to helping us make progress towards a better, more civilized world. These fifth, sixth and seventh revolutions are the subject of chapter 7.

Academic philosophy, whether so-called analytic or Continental philosophy, is not noted for its fruitful implications for other areas of thought and life. How come, then, that philosophy as done here, Critical Fundamentalism, has these dramatic revolutionary implications for science, for academic inquiry, for our capacity to solve the global problems that menace our future? I do what I can to answer this question in chapters 2 and 9.

Why has academic philosophy, lost its way so drastically that it has failed to put the richly fruitful conception of philosophy, as done here, into practice? What caused academic philosophy to lose its way? I give my answer to this question in the appendix.

My chief hope, in writing this book, however, is that the reader will be beguiled or provoked into thinking imaginatively and critically – that is, rationally – about our fundamental problem, not obsessively, but from time to time.

– We are at a stage where new knowledge will have to come from a much broader collaborative effort, that collaborative effort may involve people from many different disciplines and different traditions, do you believe the philosophy of science can play a particular role in our present context?

Most scientists and philosophers of science today take one or other version of a view of science one may call “standard empiricism” for granted. This holds the following. The basic aim of science is truth, the basic method being to assess claims to knowledge impartially with respect to evidence. Considerations of simplicity, unity or explanatory power may legitimately influence what theory is accepted in addition to evidence, but not in such a way that the universe itself is assumed to be simple, unified, or such that explanations exist to be discovered (i.e. comprehensible). In science, no factual thesis about the world can be accepted as a part of scientific knowledge independently of evidence, let alone in violation of evidence.

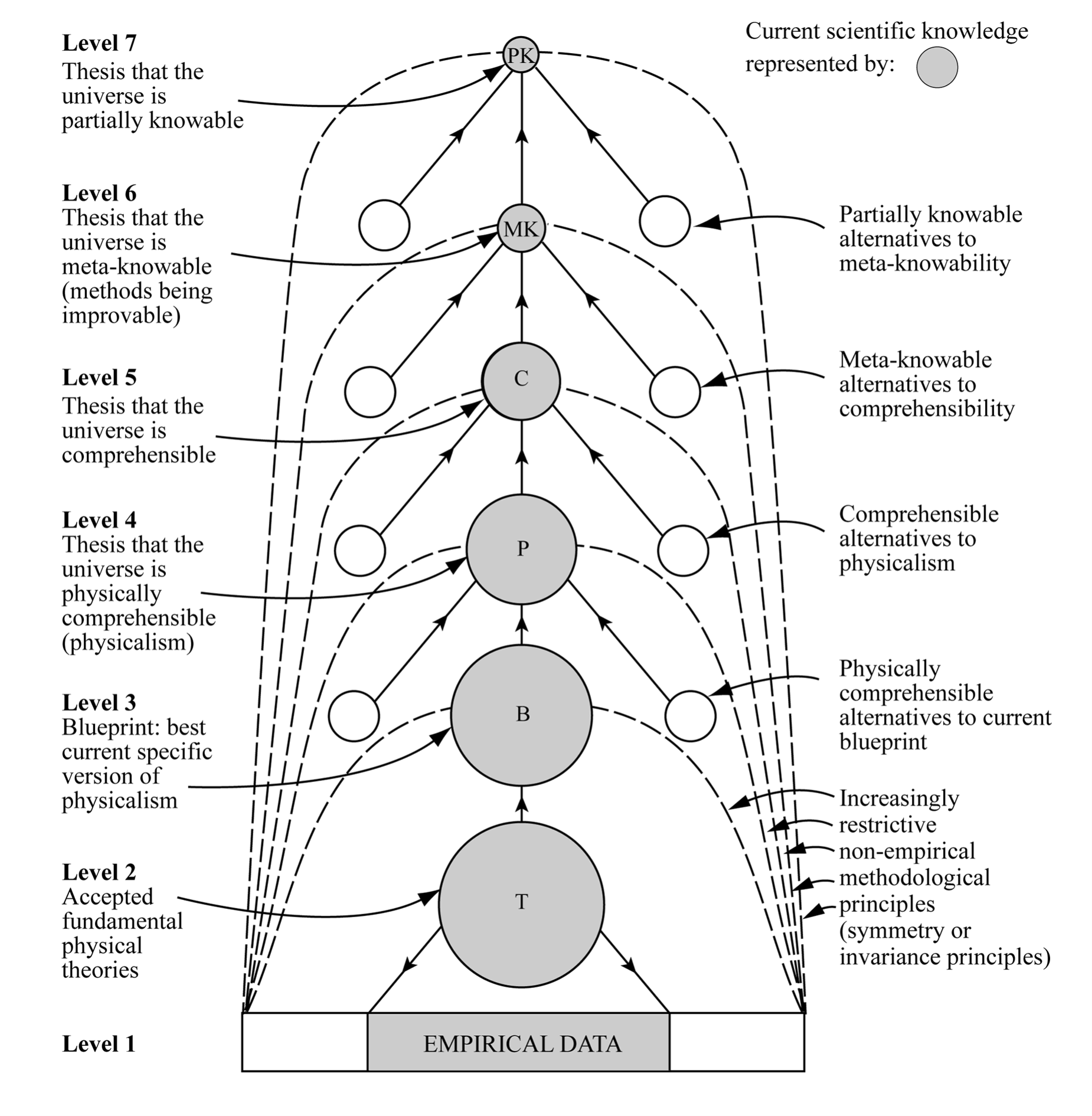

Granted standard empiricism, the role of philosophy of science in science itself must be minimal, because philosophy of science is about what ought to go on in science, and is not therefore straightforwardly empirical. But standard empiricism is untenable, as I have shown decisively, in a number of publications. (See The Rationality of Scientific Discovery, Part I: The Traditional Rationality Problem, Philosophy of Science 41, 1974, pp. 123-53; or Popper, Kuhn, Lakatos and Aim-Oriented Empiricism, Philosophia 32, nos. 1-4, 2005, pp. 181-239.) Persistent acceptance of unified theories in physics, when endlessly many empirically more successful disunified rivals always exist, means that physics makes a big, highly problematic, influential but implicit assumption: the universe is such that all disunified theories are false. There is some kind of underlying unity in nature. Physics would be much more rigorous if this highly problematic, influential but implicit assumption were made explicit, so that it can be critically assessed, and improved. I have put forward a view of science which facilitates the improvement of the at-present implicit metaphysical assumption of physics. We need to represent this assumption in the form of a hierarchy of assumptions. As one goes up the hierarchy, the metaphysical assumptions become less and less substantial (and so more likely to be true), and more nearly.

such that their truth is required for science, or the pursuit of knowledge, to be possible at all. At the top we have the thesis that the universe is such that it will be possible for us to acquire some knowledge of our local circumstances sufficient to make life possible. If that thesis is false, we have had it, whatever we assume. It can never be in our interests to reject that thesis. As we descend the hierarchy, metaphysical theses become increasingly substantial, and increasingly likely to be false, and in need of revision. As physics proceeds, we select those metaphysical theses, and associated methods, that accord with and support the most empirically progressive research programmes in physics. Thus, as physics proceeds, its assumptions and methods, its philosophy in other words, is improved in the light of improving scientific knowledge. There is something like positive feedback between improving scientific knowledge, and improving aims and methods, improving philosophy of physics. I call this view “aim-oriented empiricism”; it transforms the relationship between physics and the philosophy of physics, so that science becomes more like natural philosophy. Two of my recent books spell out this argument in detail: In Praise of Natural Philosophy: A Revolution for Thought and Life, 2017, McGill-Queen’s

University Press, Montreal; Understanding Scientific Progress: Aim-Oriented Empiricism, 2017, Paragon House, St. Paul, MN. See also Aim-Oriented Empiricism and the Metaphysics of Science. Philosophia, 48, 2020, pp. 347–364.

The basic aim of physics is problematic because it has a problematic thesis inherent in it, all too likely to be more or less false, namely that the universe is physically comprehensible in some way or other. Because of the problematic character of the basic aim of physics, we need to put aim-oriented empiricism into scientific practice, in an attempt to improve the aims and methods, the philosophy, of physics as we proceed. And, more generally, the aims of science are problematic because they have problematic assumptions inherent in them, having to do with metaphysics, values, and the social use of science. Aim-oriented empiricism needs to be put into scientific practice throughout science, to give us our best chances of improving the aims and methods of science as we proceed, so that we develop science in directions of greatest value to humanity.

It is not just science that has profoundly problematic aims, that need to be improved as we proceed. This is the case in life too. Many of our personal, social and institutional endeavours have problematic aims that need to be improved. Government, industry, agriculture, law, the media, education, international relations, all have problematic aims that need to be improved. Aims can be problematic because they have unforeseen, undesirable consequences, because they clash with other desirable aims, or because they cannot be achieved. Aim-oriented empiricism – scientific method as it ought to be conceived – can be generalized to form a conception of rationality – aim-oriented rationality, fruitfully applicable to all worthwhile human endeavours with problematic aims. I argue in my work that a basic task of social inquiry and the humanities ought to be to help humanity get aim-oriented rationality into personal, social and institutional life, into government, industry, agriculture, etc., so that we discover how to improve problematic aims and methods as we live, thus making progress towards, a good, civilized, wise world. We have something very important to learn from scientific progress, in other words, about how to make social progress towards a better world.

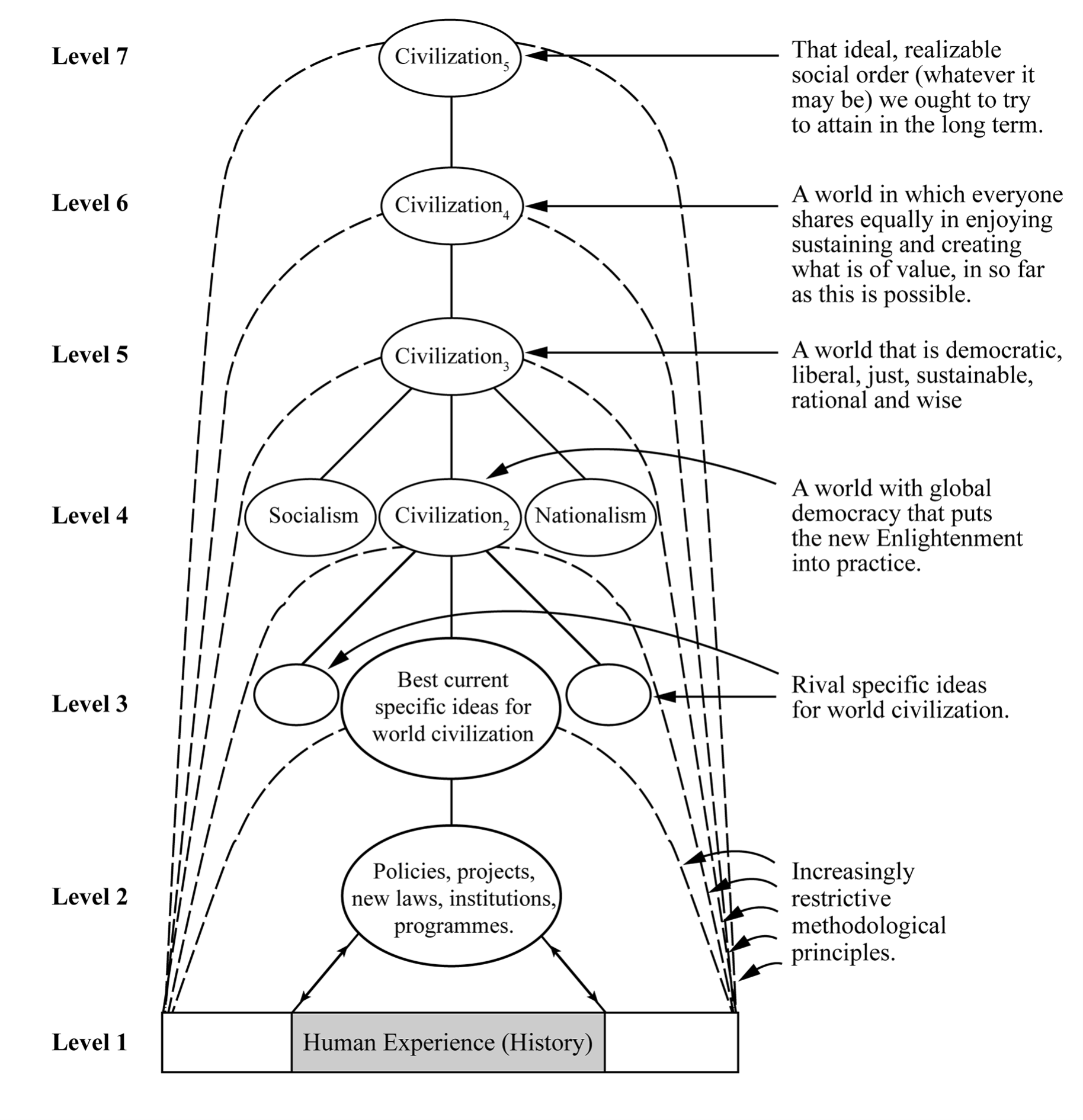

For a diagrammatic representation of aim-oriented empiricism see the first of the above two diagrams. For aim-oriented rationality (generalizing aim-oriented empiricism), applied to the task of making progress towards a civilized, enlightened world, see the second of the above two diagrams.

– Do you consider what we call the great accomplishments in modern science became highly problematic because of the new developments in science? Should science be distinguished from the other types of knowledge? Meanwhile, can a meaningful distinction be drawn between natural sciences and social ones?

I see things in the following way. Humanity faces two great problems of learning: learning about the nature of the universe and our place in it, and learning how to become civilized. The first problem was solved, in essence, in the 17th century, with the creation of modern science. But the second problem has not yet been solved. Solving the first problem without also solving the second puts us in a situation of great danger. All our current global problems have arisen as a result. The lethal character of modern war, pollution of earth, sea and air, vast inequalities in wealth and power around the world, destruction of natural habitats, catastrophic loss of wild life, and mass extinction of species, the menace of nuclear weapons, and perhaps most serious of all, the climate crisis: all these global problems have arisen because we have modern science and technology, but do not have genuine civilization. Now that some of us have the immense power to act that modern science and technology make possible, lack of wisdom has become a menace. What we need to do, in response to this unprecedented crisis, is learn from our solution to the first problem how to solve the second – learn from scientific progress how to make social progress towards a wiser world. This was the basic idea of the 18th century Enlightenment. Unfortunately, in carrying out this programme, the Enlightenment made three blunders, and it is this defective version of the Enlightenment programme that we have institutionalized in 20th century academic inquiry. In order to solve the second great problem of learning we need to correct the three blunders of the traditional Enlightenment. This involves changing the nature of social inquiry, so that social science becomes social methodology or social philosophy, concerned to help us build into social life the progress-achieving methods of aim-oriented rationality, arrived at by generalizing the progress-achieving methods of science. It also involves, more generally, bringing about a revolution in the nature of academic inquiry as a whole, so that it takes up its proper task of helping humanity learn how to become wiser by increasingly cooperatively rational means. The scientific task of improving knowledge and understanding of nature becomes a part of the broader task of improving global wisdom.

What we suffer from, then, is science without wisdom. Modern science gives (some of) us enormous power to act, but not enhanced power to act wisely. As a matter of supreme urgency, our universities need to take, as their basic task, to help humanity learn how to tackle our grave local and global problems of living in increasingly cooperatively rational ways, in increasingly wise ways.

Can natural and social science be distinguished? In my view, most certainly. Social science ought not, in my view, to be pursued primarily as science at all. As I have indicated, social inquiry ought to be social methodology, or social philosophy, concerned to help us resolve conflicts and problems of living in increasingly cooperatively rational and wise ways. It has the task of helping us get aim-oriented rationality into the fabric of personal, social and institutional life. Social inquiry pursues knowledge in order to get clearer about what our problems of living are, and in order to assess proposed solutions to our problems – actions, policies, political programmes, philosophies of life. Both natural science and social inquiry should seek to help promote human welfare, but ideally they do that in different ways.

– It is not clear yet why you think that science can free society from poverty, hunger, etc., do you think that the radical new approach you argue able to change the people feel and think? What do you think of the obstacles that stopping this solution?

Modern science and technology have done a great deal to free the world of poverty, hunger, and ill-health, via modern methods of agriculture, modern medicine, and in many other ways. But poverty, hunger and ill-health remain as all-too prevalent features of our world. And our very successes in tackling these conditions have created new problems. Modern medicine and hygiene have led to rapid population growth. Modern agriculture, combined with population growth, has led to habitat destruction, loss of wild life and impending mass extinction of species. Modern power production and travel have led to climate change. Modern industry, agriculture and our whole way of life have led to pollution of earth, sea and air – plastic everywhere in the oceans. And modern science and technology have led to modern armaments, including nuclear weapons, and the lethal character of modern war. All this illustrates the point I have already made: science without wisdom is, potentially, a menace. Modern science and technology enormously increase our power to act, but not our power to act wisely. What we urgently need, today, is institutions of learning, schools and universities, devoted to helping us learn how to resolve our conflicts and problems of living in increasingly cooperatively rational ways. Universities need to put problems of living at the heart of the enterprise, and need to concentrate on discovering and promoting good, effective, wise solutions to such problems – personal, social and political actions designed to solve our problems of living. The scientific pursuit of knowledge would be important, but secondary.

A basic task of universities ought to be to promote public education about what our problems are, and what we need to do about them, by means of discussion and debate.

What obstacles are there in putting this wisdom-inquiry idea into practice? First, academic philosophers need to be persuaded to take up philosophy as Critical Fundamentalism. Second, the scientific community needs to be persuaded to abandon the pretense that science proceeds in accordance with standard empiricism, and instead adopt and implement aim-oriented empiricism in scientific practice. Third, those working in the fields of social science and the humanities need to be persuaded that their proper basic task is to help promote increasingly cooperatively rational resolving of conflicts and problems of living in the social world. They need to be persuaded, too, that they have the basic task of helping humanity get aim-oriented rationality (arrived at by generalizing aim-oriented empiricism) into social life – into government, industry, agriculture, social media, etc. Fourth, the whole academic enterprise, universities around the world, need to be persuaded to put wisdom-inquiry into practice. Finally, there is the really vital and immense task of progressively reforming the social world so that we all succeed in implementing something like wisdom-inquiry in our lives – personal, social, institutional. There are major obstacles to all these initiatives – obstacles of inertia, vested interests, dogma, power, wealth. I have been working hard at achieving the first step for some 45 years, and I have only had very modest success so far. I did create Friends of Wisdom in 2003, an international emailing group of academics and educationalists all devoted to the idea that universities should seek wisdom. And UCL, and some other universities, have taken modest steps towards wisdom-inquiry. But almost everything remains to be done!

– Am I right that in terms of the present understanding for the philosophy of science, nothing can be said about Empiricism? You have a book entitled ‘Metaphysics of science’ could you shed light on what made you interested in this issue?

The full title of my book is The Metaphysics of Science and Aim-Oriented Empiricism: A Revolution for Science and Philosophy, 2019, Synthese Library, Springer, Switzerland. It gives an account of my work, from my first paper published in 1966 to my most recent work Amongst other things, it gives an account of aim-oriented empiricism – definitely a version of empiricism! My interest in the metaphysics of science arose, in part, out of my concern to make sense of science. Karl Popper claimed to solve the problem of induction, but he failed to do that, essentially because he failed to appreciate that persistent preference in science for unified theories means that science makes a big, problematic metaphysical assumption about the nature of the universe: it is such that all disunified theories are false. There is some kind of underlying unity in nature. As I have already explained, precisely because this assumption is influential and profoundly problematic, to the extent of almost certainly being false in the specific form it is implicitly accepted at any stage in the development of science, it is vital that this assumption is made explicit within science, so that it can be critically assessed and improved. Aim-oriented empiricism emerges as the best procedure for improving the metaphysical assumptions of science, as science proceeds. Aim-oriented empiricism succeeds in doing what Popper failed to do: it solves the problem of induction. It exhibits science as a rational enterprise. And it can be generalized, to form a conception of rationality – aim-oriented rationality – specifically designed to help us improve problematic aims as we act, fruitfully applicable to all worthwhile human endeavours with problematic aims.

– Under the heading of “what’s wrong with Science?’ you offer a new theoretical approach to the relationship between science and humanity, science, and institution, in general, science and society. Do you think if we decrease the tensions that are actually happening between science and other forms of knowledge, we can overcome these tensions? How?

My basic argument is that knowledge-inquiry (academia devoted to the pursuit of knowledge) needs to become wisdom-inquiry (academia that seeks fundamentally to solve problems of living, problems of poverty, injustice, war, and environmental degradation, and in order to do that, proposes and critically assesses possible actions, policies, political programmes, the pursuit of knowledge being important but secondary). The transition from knowledge-inquiry to wisdom-inquiry transforms the whole relationship between academia and the social world. What really matters is wisdom-inquiry going on in the social world – the thinking we engage in as we live, guiding our actions. We need to see universities as a resource to help us improve our thinking guiding our actions in life. Universities implementing wisdom-inquiry would be a kind of people’s civil service, doing openly for the public what actual civil services are supposed to do, in secret, for government. Universities and the public would be engaged in discussion and debate about what our problems are, and what we need to do about them. Ideas, arguments and experiences would go in both directions, from the public to the university, and vice versa. The relationship between science and society, academic inquiry and society, would be transformed.

– One of the areas you discussed in your works was the question of “Objectivity”, could you shed the light on this issue, especially we have many schools in the philosophy of science have rejected it?

Some philosophers have been tempted to deny that the world exists objectively, independently of what we think about it. Long ago, I came across a passage in Popper’s Conjectures and Refutations which convinced me that this was both wrong and harmful. Popper says:-

“The belief of a liberal – the belief in the possibility of a rule of law, of equal justice, of fundamental rights, and a free society – can easily survive the recognition that judges are not omniscient and may make mistakes about facts and that, in practice, absolute justice is hardly ever realized in any particular case. But this belief in the possibility of a rule of law, of justice, and of freedom, can hardly survive the acceptance of an epistemology which teaches that there are no objective facts; not merely in this particular case, but in any other case: and that the judge cannot have made a factual mistake because he can no more be wrong about the facts than he can be right.” Conjectures and Refutations, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1963, p. 5.

I found this argument wholly convincing; and I am still convinced. The world exists independently of us, although we are, of course, a part of it. If we deny that the world exists objectively, we endanger such precious things as justice and freedom. We do not even have an argument against the powerful when they decide, in their own interests, what is true and what is false. I might add that I have argued, not just for objective facts, but also for objective values: see “Are There Objective Values?”, The Dalhousie Review, 1999, vol. 79 (3), pp. 301-317: https://philpapers.org/rec/MAXATO . If what is of value exists objectively, we need to hold our value judgements as conjectures, not dogmatic certainties. The following consideration convinces me that what is of value does have an objective existence. A good person lives and dies. No relative, friend or acquaintance appreciates all that is of value associated with this person’s life, not even the person himself or herself. Yet, it seems to me, it exists. The view that what is of value is subjective carries the dreadful implication that what is of value in people’s lives that is not perceived, simply does not exist. I find that unacceptable.

– There has been a lot of debate in recent days about the rereading the western Enlightenment program; how do you see the role of ideals of the western Enlightenment still play a useful role in today’s circumstances?

In my view, the basic idea of the 18th century Enlightenment was to learn from scientific progress how to achieve social progress towards an enlightened world. I hold that to be a profoundly important idea. It is absolutely vital, however, to develop and implement this idea correctly. Unfortunately, the philosophes of the Enlightenment – Voltaire, Diderot, Condorcet and others – in developing the basic idea, made three dreadful blunders. They developed the basic idea in a dreadfully botched form. First, inspired by Newton, they accepted a crude inductivist version of standard empiricism as the proper way to construe scientific method. Second, having got scientific method wrong, they failed to generalize it correctly, to form a conception of rationality, applicable fruitfully to all that we do. And third, instead of seeking to apply reason directly to social life in an attempt to make progress towards an enlightened world, they applied it to the task of acquiring knowledge about the social world, to the task of creating and developing the social sciences, in other words: economics, anthropology, psychology, sociology, political science. This botched version of the Enlightenment idea was then developed throughout the 19th century by J.S. Mill, Karl Marx, Max Weber, and others, and built into the academic enterprise in the early 20th century with the creation of academic departments and disciplines of social science. The outcome is what we have today, knowledge-inquiry, academia devoted in the first instance to the pursuit of knowledge. A recently published book that praises this botched version of the Enlightenment, and fails entirely to recognize the three disastrous blunders that are inherent in it, is Steven Pinker’s Enlightenment NOW, 2018, Allen Lane. For my decisive criticism of this book see We Need Progress in Ideas about how to achieve Progress, Metascience, 2018, vol. 27, issue 2, pp. 347-350.

What, then, are the three blunders of the Enlightenment, and what needs to be done to put them right? The first blunder is to fail to get the progress-achieving methods of science into focus. The correct way to construe the progress-achieving methods of science is, not in terms of standard empiricism, but in terms of aim-oriented empiricism, as I have already argued. Science needs to acknowledge its real, problematic aims, and needs to try to improve these aims as it proceeds. The second blunder is to fail to generalize the progress-achieving methods of science properly. In order to do that correctly, we need to generalize aim-oriented empiricism to form aim-oriented rationalism. It is not just science that has problematic aims. Our aims are often all too problematic in personal, social and institutional life too. Aim-oriented rationality has the great merit that it is designed to help us improve our aims, whatever we may be doing, when we need to do that, in order that we may achieve what is of real value in life. The third blunder is to apply generalized scientific method to the task of acquiring knowledge of the social world – to the task of creating and developing the social sciences in other words. What needs to be done instead is to apply aim-oriented rationality directly to social life, to government, industry, agriculture, social media, the law, and so on, in such ways that these endeavours, instead of creating problems, become social engines working away to help us make progress towards a good, enlightened world.

Much of my work has been devoted to pointing out that many of our current global problems, and our failure to discover how to resolve them, is due to the fact that our institutions of learning, above all our universities, are deeply flawed because they have in them structural blunders we have inherited from the Enlightenment. We urgently need, as the title of my review of Pinker’s book states, progress in ideas about how to achieve progress!

– You have been researching the new concept of science, in the light of what you are arguing, and where are the values within science in your project? In other words, do you see a philosopher has a moral and social responsibility?

All of us should have a moral and social responsibility – although the greater one’s influence or power, the more it matters. Basic values inherent in science ought to be intellectual integrity, respect for fact and truth, and to do research in the hope that it is of benefit to humanity, culturally or in practical ways.

– Can the scientific community function as moral authority in a society? If scientists can tell us how many people COVID19 will probably kill, can they also tell us what human activities are ‘essential’ enough and what are not ‘essential’ enough to risk people dying? And if they cannot, then what does it mean for people to say we should ‘listen to the scientists’?

I do not think the scientific community can function as a moral authority. Nor should academics working within the framework of wisdom-inquiry – should such a thing ever come to pass – function as moral authorities. What such academics might have to propose about how we should go about solving our problems should be listened to; but what they propose should be judged on the merit of what is proposed, not on the basis of who makes the proposal. Even when scientists confine themselves to scientific, factual matters, ultimately what matters is the intrinsic merit of what is said, the reasons there are for taking it seriously; it should not be believed just because it is uttered by a scientist. Scientific experts sometimes get things wrong. The current pandemic provides examples of that – certainly in my country, the UK.

– Many have admired what you call ‘Wiser World’ and many have criticized, could you highlight this term?

“A wiser world” for me, strictly speaking, would be a world in which more people, social groups and institutions have a greater capacity and desire, and a greater active endeavour, to achieve what is genuinely of value in life, for themselves and others. In my work, however, I have tended to use “wiser world” to stand for the good, civilized, enlightened world that we should seek to achieve. What should we take such a world to be – a world that is both attainable and as good, civilized, or enlightened as possible? As I have already stressed, our aims in life are often problematic, and that applies especially to this long-term aim for humanity: to achieve a genuinely wise, good world. Aim-oriented rationality recommends that we represent this aim as a hierarchy of aims – mirroring the hierarchy of aims of aim-oriented empiricism: see the two diagrams above. In the diagram representing aim-oriented rationality devoted to achieving a wise world, there is a hierarchy of five characterizations of the aim of “wise world” or “civilized world”, which become increasingly specific, and increasingly controversial and problematic, as one goes down the hierarchy. At the top, I characterize a civilized world as “that ideal, realizable social order (whatever it may be) we ought to try to attain in the long term”. That is so vague, so unspecific, that hardly anyone is going to disagree with that characterization of a wise or civilized world. Next down we have “a world in which everyone shares equally in enjoying, sustaining and creating what is of value, in so far as this is possible”. A bit more controversial. Not everyone may agree with equality as an ideal, in so far as it is possible. Next down we have “A world that is democratic, liberal, just, sustainable, rational and wise” (wisdom here to be construed as I have already characterized it). This is more problematic, more controversial. Next down in the hierarchy, we have “a world that has global democracy that puts the new Enlightenment into practice” (the Enlightenment with its three blunders put right). Still more would object to this. But it is in that kind of way that I would characterize any ideal problematic state of affairs we hope to attain: as a hierarchy, an unspecific, uncontroversial, unproblematic aim at the top, and then aims becoming progressively more specific and more controversial and problematic as one goes down the hierarchy. For more details see my How Wisdom Can Help Solve Global Problems. In Sternberg, R., Nusbaum, H., Glueck, J. (Eds.), Applying wisdom to contemporary world problems. 2019, pp. 337-380, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

There is one feature a “wise world” ought to possess, in my view, that the above does not mention, namely that, as far as possible, political, economic and social life run along cooperative lines. That is an explicit theme of my From Knowledge to Wisdom: see https://philpapers.org/rec/MAXFKT-2 .

– What convinces you that we suffer not from too much scientific rationality, but too little? Do you think the concept of Scientific Rationality’ is problematic?

The scientific community takes standard empiricism for granted. For scientists, standard empiricism is scientific rationality. But standard empiricism is untenable. It holds that the basic intellectual aim of science is truth as such, when actually it is truth presupposed to be explanatory – or explanatory truth. There are problematic metaphysical assumptions inherent in the aims of science, and problematic assumptions concerning values and politics too. (More generally, science seeks truth that is of value or use in some way; and, ideally, it seeks valuable truth so that it will be used by people, in cultural or practical ways, to enhance the value of human life.)

To attempt to pursue science in accordance with standard empiricism is to undermine the intellectual rigour, the rationality, of science. For it leads to the suppression of influential, problematic metaphysical assumptions – and assumptions about values, and the social use of science, as well. A basic requirement for intellectual rigour is that influential and problematic assumptions be made explicit so that they can be critically assessed and, we may hope, improved. Science that seeks to conform to the edicts of standard empiricism violates that requirement for intellectual rigour. Science pursued in accordance with aim-oriented empiricism would, however, satisfy that requirement for rigour. That is the whole idea of aim-oriented empiricism: to make explicit, and so criticizable and improvable, problematic assumptions that are at present implicit.

How do we suffer from this current irrationality of science? In two ways. First, science, and the human value of science, suffer. In order to give ourselves the best chances of scientific success, we really do need to subject implicit metaphysical assumptions of science to sustained imaginative and critical scrutiny. (I have spelled out how this can be done in In Praise of Natural Philosophy: A Revolution for Thought and Life, 2017, McGill-Queen’s University Press, chapter 5.) Science constrained by standard empiricism does not do that and, as a result, suffers (in ways discussed in the book just indicated). The progress of science is adversely affected. Furthermore, science influenced by standard empiricism does not recognize the vital need for the imaginative and critical exploration of actual and possible research aims for science, in the hope of discovering those that will lead to discoveries and developments of real benefit to humanity – of benefit especially to those whose needs are the greatest, the poor of the earth. As a result of this failure, science tends to develop in ways that benefit most the wealthy and powerful, those who fund science, rather than those whose needs are the greatest. Diseases of the wealthy get more scientific attention than diseases of the poor.

There is an even more important way in which we suffer from the irrationality, the lack of rigour, of standard empiricism. As long as we accept standard empiricism, with its fixed aim of truth, we cannot arrive at the idea that a generalization of scientific method would result in a conception of reason designed to help us improve problematic aims as we act. We cannot arrive at aim-oriented rationality, in other words. And indeed, current conceptions of reason are all about means, not about improving ends. But we desperately urgently need to adopt and put into practice a conception of reason that does help us improve problematic aims as we act. We suffer from the failure to do just that. We pursue industrial and economic progress, and create the climate crisis, and destroy the environment. We pursue health, and create the population explosion. We build up our armies, our weapons, and provoke other nations to do likewise, undermining security, and increasing the likelihood of war. We create nuclear weapons to end war, and thereby endanger the future of humanity. We urgently need to discover how to improve problematic aims and ideals in our personal, social and institutional lives. Science ought to be a model, an ideal, of how to do that. Standard empiricist science, because of its lack of rationality, is nothing of the kind.

Do I think the concept of scientific rationality is problematic? No, I don’t. Construe science in terms of aim-oriented empiricism, and problems about scientific rationality disappear. These problems are created by the attempt to conceive of science in terms of standard empiricism.

– Since the early seventeen century of Francis Bacon, Galileo Galilei, and René Descartes, the relations between Science and Religion have remained volatile sites of conflicts, how do you consider this issue? And do you think there is a place for religious faith within science?

The relationship between science and religion is indeed complicated. Galileo famously ran into difficulties with the Church of Rome. However, both Kepler and Galileo seemed to have interpreted the simple mathematical laws they believed governed natural phenomena as a manifestation of God’s will. Almost all those associated with the birth of modern science believed in God, and that belief played a role in justifying the possibility of science. God, it was believed, would have created the universe to be comprehensible to humanity, and thus make science possible.

I don’t think there is a place for religious faith within modern science, but I certainly believe there is a place within science for scientists who have religious faith. Science is, however, a part of academic inquiry, and the latter, if implementing wisdom-inquiry, could be interpreted as a religious enterprise, devoted as it would be to helping that which is of authentic value in life to flourish. I personally do not believe in God, essentially for the following reason. An all-powerful, all-knowing God would be knowingly responsible for all natural phenomena that cause human suffering and death. I do not think anything can excuse that. For me, a life of religious faith involves living life lovingly.

What are the key messages that you like to send to the philosophers in the Middle East?

All around the world universities, in giving priority to the pursuit of specialized knowledge, betray reason, and as a result, betray humanity. Our current incapacity to resolve the grave global conflicts and problems that threaten our future is the result of this academic betrayal. We need urgently to bring about a revolution in universities so that the basic task becomes, not just to acquire knowledge, but rather to seek and promote wisdom – wisdom being the capacity, active endeavor and desire to realize what is of value in life for oneself and others, wisdom in this sense including knowledge, understanding and technological know-how, but much else besides. Instead of giving intellectual priority to solving problems of knowledge, universities need to give priority to helping solve conflicts and problems of living – above all, the global problems, such as the climate crisis, that threaten our future. It is all-important that humanity learns how to resolve conflicts and problems of living in increasingly cooperatively rational, wise ways. But if that is to happen, we need our universities to be designed and devoted to helping bring it about. Universities need to take, as a basic task, public education about what our problems are, and what we need to do about them. Social wisdom is essential for our survival. Before the advent of modern science, lack of wisdom did not matter too much. We lacked the power to act to do too much damage to ourselves or the planet. But now that we do have modern science and technology, and all the power to act that they bequeath to us, lack of wisdom has become a menace. The touch of a button could annihilate humanity. We must become wiser. But for that to happen, it is absolutely essential that we bring about the academic revolution I have indicated, so that universities take up the task of helping all of us – our social world – become wiser. (See How Wisdom Can Help Solve Global Problems and my website: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/from-knowledge-to-wisdom/ .)

Finally, Professor Maxwell, we have benefited greatly from discussions and conversations with you. Heartfelt thanks to you.

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to answer your questions.

ترجمة: محمد كزوّ - تحرير ومراجعة: بلقيس الأنصاري حتَّى عندما تعلَم أنّ الآفاق قاتمة، فالأمل يستطيع مساعدتك؛ إنَّه ليس مجرَّد...

«لقد أثبتت السينما بأنّ لها قُدرة فائقة على التأثير. واليوم من خلال هذا المهرجان؛ نتعاون جميعًا لتعزيز اسم الخليج العربي...

لا عجبَ ألا يملك الأسقف بيركلي وقتًا للحسّ المشترك، فهو الرّجل الذي أنكر وجود المادّة. لقد اشتكى في كتابه «مبادئ...

إن الفلسفة غير معنية بالوضوح أو بتقديم أي إجابات واضحة عن الإنسان والعالم. هناك مقاربات وتيارات فلسفية هي أشبه بلعبة...

«معنى»، مؤسسة ثقافية تقدّمية ودار نشر تهتم بالفلسفة والمعرفة والفنون، عبر مجموعة متنوعة من المواد المقروءة والمسموعة والمرئية. انطلقت في 20 مارس 2019، بهدف إثراء المحتوى العربي، ورفع ذائقة ووعي المتلقّي المحلي والدولي، عبر الإنتاج الأصيل للمنصة والترجمة ونقل المعارف.